December 28 2025

There is a scene from Dread Beat an Blood, Franco Rosso’s 1979 film about Linton Kwesi Johnson, that plays in my head. Of the film, Johnson recently wrote, “I was working at the Keskidee community and arts centre in Islington as a librarian and educational resources officer, having just completed a nine-month stint as writer-in-residence in the London Borough of Lambeth. The timing was as propitious for Franco as it was for me. As a member of the Race Today Collective and the Black Panther Movement, I was involved in a justice campaign for George Lindo, a Jamaican from Bradford who had been wrongfully convicted of robbery. I was also involved in the occupation of my local youth and community centre in Brixton, which the new warden for the Methodist church was trying to shut down because he resented the autonomy of the youth club members. Moreover, I had signed a deal with Virgin records and began to record my first reggae album, Dread Beat An’ Blood.”

The scene I think of takes place at Keskidee. Young mean are circled around a table, playing cards and smoking, talking with Johnson about policemen harassing them and breaking up a “blues dance” just for kicks. Johnson asks, “Do you think that when English people decide that we going to have a little social get together, have a party, anything, you think that the police have that kind of attitude to them?”

This stayed with me not because Johnson told them something they didn’t know or proved that funding for community arts programs is essential, though both things might be true. (I interviewed Johnson a few months ago and that talk is reproduced at the end of this newsletter.) The scene replayed because it showed a small group of people discussing something important, in real time, in person. The way forward involves doing this and also treating our internet spaces with the same care. We cannot, actually, fully disembody ourselves.

Two years of genocide have brought unsurprising changes, like an increased sensitivity to the cables of empire snaking around your life and your friends (sometimes with their consent). The constant chime of death also has the effect of an extended release grief pill, making God’s manifestations that much brighter and juicier. If people are confused about the resilience of the resistance, they are resisting the gift of acceptance. How will you live before you die?

Many of the answers are variations of “being with family and friends.” This is what I think about when I see Johnson with the men at Keskidee. If there is a horizon, an ideal, it lives coupled with a view of daily life. The mundane comes first: small, iterative tasks and habits you find yourself grateful to have. (Not everything submits to a pathology.) Cards, smoking, reading, schemes. If we see the small efforts made in America on behalf of Palestinians slurried down the drain with yet more art world gossip, take solace—tonight, you are with your friends, and this is what you hope for everyone.

If I am able to keep a pledge to myself, 2026 will find me detaching from the platforms that commercial actors nurtured and handed over to the surveillance state. I’m a goof for renting my music back from Apple and I am equally dumb for letting Google read all my chaotically-formatted Kropotkin epubs! The next phase of living with clunky NAS servers and shared drives will strip out the microphones serving us olive oil ads and allow us to more fully mirror our family networks. Inshallah, we can all do a parallel group watch of Peter Wollen’s Friendship’s Death. In that direction, my friend, Sunny Iyer, made this downloadable mix, blue blue electric blue. Here is her description:

“this is a holiday playlist that tends toward bells, echoes, rain, chimes, dramatic vocals, end of year big feelings, on the precipice of a new year.

the first half is slower and quieter, ambient to kraut with lots of ethereal flourish like enya’s christmas secret and daffy's cover of moby. feels like leaping off a cliff and discovering you can fly. the second half is the kind of music i like to play with family around, easy listening and recognizable (jam band, linda ronstadt, joan armatrading, roxy music, a van morrison song i wish was twenty times longer). no matter the time of year, every time i listen to bowie's sound and vision it feels like xmas morning. blue blue electric blue... slipping around in socks in the morning. jesus is in there too, because it's his birthday.

this is what i'll listen to in the kitchen all christmas eve and day, sleepily washing and cutting vegetables, energy crescendo as the pace quickens and we're making sauces and dressings, entrees, then homemade peppermint ice cream--my favorite flavor. i'll open a bottle of cold wine at the start of the 14 minute neil young song and another at the 20 minute blue gene tyranny denoument. everything gets a bit silly and emotional from there on. my favorite elvis xmas song at the very end.”

Our friends figure stuff out. Maybe one them figured out how to download all of Spotify. I would hate to be the one to recommend you click that link and do that! A better use of an hour might be watching this video my friend Sina just published, and which involved several months of work: Mohammed and Mahmoud talking about their life in Gaza.

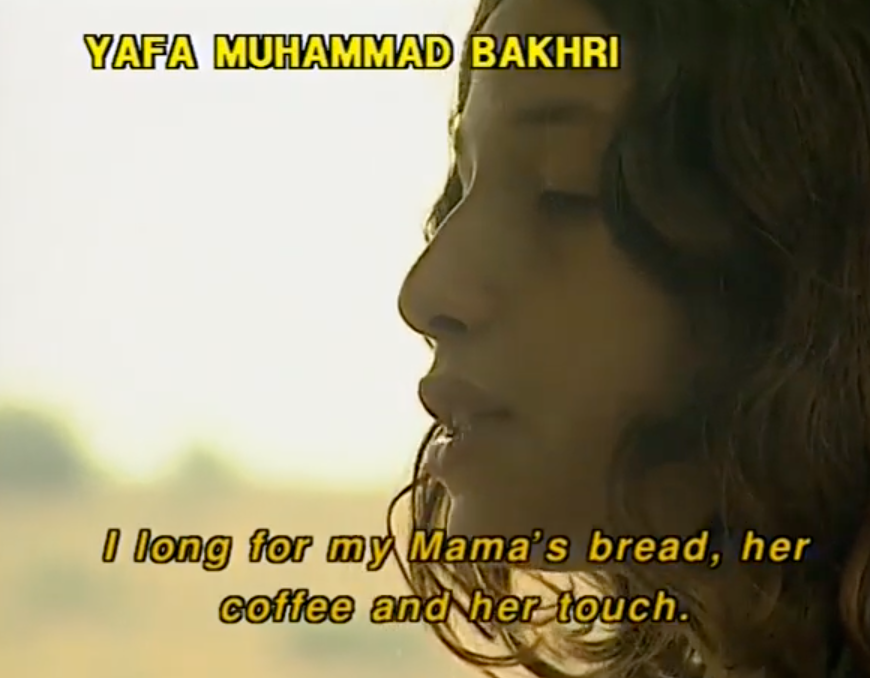

Sometimes your first (and last) friends are family members. The world just lost Palestinian actor and director, Mohammad Bakri. (Watch Jenin, Jenin right now if you never have.) Bakri’s 1998 film, 1948, is narrated by the people who lived through 1948, and towards the end, his daughter Yafa sings a song.

Yafa’s singing was the second instance of family music I heard this year. In February, a symposium devoted to Etel Adnan took place at Giorno Poetry Systems and The Poetry Project. On the very first day, organizer Omar Berrada introduced his daughter, Safira, who opened the series by playing two compositions by Mohammed Abfel Wahab for oud: “An-nahr al-khaled [the eternal river]” and “Ya msafer wahdak [O lone traveler].” I often feel self-conscious saying phrases like “the imperial core,” as if I would have any idea where the borders of that core begin and end. That day, though, hearing Safira’s oud make me think the core was melting. I am sure it has reconstituted itself by now.

Idris Robinson sent me this three-hour video by Adi Callai, posted on Christmas: WHAT-DO. Am I going to tell you that I can co-sign all ten theses presented in this call for revolutionary tactices? No. But give me another watch or two, and I might. That a comrade can still get something like this onto the shelf of YouTube tells me it is still worth keeping tabs. (The uncensored version of this video is on Callai’s Patreon page.) This is where we are now, balanced on a small stack of services that might eliminate us at any moment. Buttondown will not delete this newsletter, though. That much I can guarantee.

And, of music, what did friends talk about? Chuquimamani-Condori. Pitchfork’s album of the year was Los Thuthanaka, a collaboration between Chuquimamani-Condori and their brother, Joshua. The music is blown-out keyboards and kicks, an ancient future music born in Bolivia and growing like a vine throughout the southwest corner of America. I am more familiar with these five NTS mixes, which feel as radical as anything out there. Chuquimamani-Condori’s Precious Memories is a detournement of Nashville masculinity and an invocation that summons the pantheistic roots of Christianity. Honestly—these C-C music factory mixes feel like scientific evidence of a new emotion, a substrate of commercial country radio that connects to all known religions. Here are download links that Chuquimamani-Condori posted in their Instagram story: Precious Memories, Find Me, the uru uru golden child E DJ edit, and Bethlehem.

Jeremy Larson wrote about Los Thuthanaka for the Pitchfork year-end list and, as coincidence would have it, his recent DJ set at Public Records has been playing here in our house. Philip Sherburne also alerted me through his newsletter that an old friend, Craig Willingham, is back as Swarm of Bees. Their one posted mix is seamless and deep dance music, and if you don’t know his old work as I-Sound and Wasteland, look it up.

If friends have been a difficult topic for you, consider this existential guide to making friends, sent to me by two different friends. A sample:

Practice asymmetry without accounting.

You will text first, often. Later they will. Then you again. If you keep a ledger, you are an auditor, not a friend. The universe does not balance; the kindness must.

My friend Amanny and I like to talk about the teen Slovenian dance phenom, Ian Hotko, and a chunk of mutuals go nuts every time I post him. Other friends love the “Bitch” demo leaked from D’Angelo’s Voodoo days, yet another excuse to keep mourning and celebrating. And the Lisette Melendez “Together Forever” Berrios beats edit? Thank you to Dave Tompkins, a friend for many, many years.

Dread Beat an Blood is touring cinemas in the US and Canada now and will be available on streaming and physical media after that. (Please check out Seventy-Seven’s site and/or Instagram for more information.) Hearing Johnson’s voice is as important as hearing his words, so listen to this radio interview conducted the day before I talked to Johnson.

SFJ: Are there things that jump into your head when you watch the film now?

LKJ: I don’t watch it. I’ve seen some stills from it and all I can think is, “My God, you've grown ugly over the years. You've deteriorated immensely! You were a good-looking guy!”

SFJ: Nothing’s changed.

LKJ: It was an important initiative on the part of the late Franco Rosso because I had just started out as a poet. I had two publications but only one proper book out, and was just beginning to learn my craft. I was also starting to make records as a way of trying to reach a wider audience with the verse I was writing. My inspiration were the reggae DJs.

I’ve talked about my favorite being Big Youth back in the day. I guess there've been better DJs that came along after Big Youth, but at that time he was the man as far as I was concerned. I wasn’t a Rasta but I was identifying with Rasta. I was attracted to its anti-colonial sentiments as a young activist. Big Youth was a guy who brought Rasta talk into the DJ and lyrics.

SFJ: I think maybe the first reggae record I bought was yours.

LKJ: Which one? Dread Beat an’ Blood or Forces of Victory?

SFJ: LKJ in Dub. Then I got Dread Beat an’ Blood. I found everyone else through you—Big Youth, U-Roy, Dr. Alimantado, all of these records.

LKJ: Dr. Alimantado—I wonder whatever happened to him? He was in London back in the days in the late seventies, early eighties. Best dressed chicken. He was a cool guy. I met him a couple of times.

SFJ: It seems like your political commitment was there first before you made the poems and records.

LKJ: Yeah, it was through my activism I discovered literature written by black authors. When I joined the Black Panther movement—

SFJ: The British Black Panthers?

LKJ: Yes, the British Black Panthers, but not the party—the movement.

SFJ: They’re separate cells, yes?

LKJ: Yes. There were connections but these were independent organizations. One of my first activities as a young member of the Panther Youth was to go around selling the Black Panther Party newspaper. We had our own paper as well. So in the Panthers, I discovered that black people wrote books, because there was nothing in school that gave me the slightest idea that this might be true. Black people wrote books?

SFJ: How old were you when you joined the Panthers?

LKJ: I was in my late teens, around 17. The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B Du Bois, that was the book that did it for me. I just read everything that I could get hold of.

SFJ: Were you writing poems then, or no?

LKJ: It began after reading The Souls of Black Folk. After that, I discovered a whole heap of stuff—African-American poets, novelists, poets from the Caribbean, poets from Africa. I was just reading anything that looked interesting and I was listening at the same time to music that had speech in it, like James Brown’s “Say it Loud, I'm Black and I'm Proud.” At the Panthers office, we had a record that had just come out around that time by The Last Poets. I said, “I want to do something like The Last Poets.” I wanted to do it from my Jamaican roots rather than trying to sound like a Yankee.

SFJ: That was the first time you thought about making a record?

LKJ: It was the reggae DJs that inspired me to make a record. I thought I could have some music going with my words, because people used to say to me that they sound like music. When I started out, I used to recite my poems with a percussive accompaniment. I think it was because of The Last Poets, really, because I started out just like them. They had percussion and I had percussion, too. Some guys I went to school with called themselves Rasta Love. They were interested in Rastafari. I was more interested in politics, but I embraced certain aspects of Rastafari as part of my Jamaican roots and my Jamaican heritage.

A big inspiration was an album called Groundations by Count Ossie and the Mystical Revelation of Rastafari, which was bits of history, narration and poetry, music, jazz with drums and all of that. That kind of freaked me out, blew my mind. You know it?

SFJ: Yes.

LKJ: So it was Groundations, The Last Poets, James Brown, reggae DJs and the books I was reading—that was the oral side. The books now were Notes on the Return to My Native Land by Aimé Césaire, which was part of the Negritude movement that him and Léopold Senghor and Léon Damas had founded back in the day. God, the language was just so intoxicating. I loved the elegance and the expressiveness of the French translated into English.

SFJ: What was the name of the first collection?

LKJ: Voices of Living and the Dead. It was written for voices. It's like a radio play, and it was meant to be accompanied by percussion. I got the idea from all these various sources, and Christopher Okigbo's Labyrinths, which was written much to be accompanied by flute and traditional African instruments.

Okigbo died very young in his thirties. He died in the Biafran war in Nigeria when the Eastern provinces wanted to form their own country and there was a civil war. It was horrific. A lot of people died. There was famine and all kinds of stuff and they lost the war. But Okigbo was Igbo. He was a great poet. He's the guy who was influenced by the classics. There were a lot of allusions to classical literature, Greek poetry and myths and all of that. He brought that to his native culture, his Igbo culture. The language of that, it just freaked me out, it just blew my mind in the same way that Aimé Césaire's stuff blew my mind. So a lot of the early stuff I wrote was just a lot of rubbish really, trying to write whoever I was reading at the time. It took me a while to find my own voice.

I found my voice when I made a decision to write within the Caribbean tradition, embracing the written word as well as the spoken word. I was influenced by people like Kamau Braithwaite and the poetry of Martin Carter from Guyana. In fact, I recorded two of Martin Carter's poems on an album called More Time. He's one of my favorite poets of all time.

SFJ: So you decided to write in the tradition of Caribbean poets, and you wanted the phonetic spelling.

LKJ: I wanted the reader to read it aloud. I wanted them to hear what I was hearing, but I also wanted it to look like poetry on the written paper. So I am always trying to straddle the oral and the literary at the same time.

SFJ: In the original Dread Beat an Blood poems, you also use spacings and type setting that are native to lots of poetry.

LKJ: Yeah, the pauses, the rhythms. But I was still learning my craft. I hadn't found my voice at the stage of Dread Beat an’ Blood, really. That came later. I think that came about a decade later.

SFJ: Really?

LKJ: Yeah, in the eighties. By the eighties, I don't know, by the early eighties. Like “Reggae fi Dada,” for example.

SFJ: Tell me about “Sonny’s Lettah.”

LKJ: For that poem I drew on my experience with the police, being harassed and being beaten up and all the rest of it, and the campaign to get rid of the Sus Law. All of that went into the poem, but it's imagination and an experience really. I haven't done many letter poems—just that one.

SFJ: How do you think the role of the police in Britain has changed since you wrote those poems?

LKJ: It hasn’t really changed. The Sus Law Vagrancy Act was abolished and I would like to think that my poem was a contributory factor, but it was some women in Lewisham in South East London who launched the campaign to get rid of it. The government just ended up replacing it with something similar: the Criminal Justice Act. The police were given enormous powers to stop and search people. The criminalization aspect diminished but the police still have the power to harass. It's still a big issue in the black community. If you are a black youth, you are about eight or nine times more likely to be stopped and searched by the police going about your everyday business.

Back in the day, the police would say, “I had reasonable grounds to suspect this person of attempting to steal from someone.” Now it’s just harassment. The young people, especially black youth, are not going to stand up for that kind of shit. The police will come right up into your face, and you might respond by asking “Why are you—?” and then you’re done for assault. All you have to do is touch the policeman and you’re done for assault. Back in the day, they used the planting of drugs. They can’t get away with that so easily now. People have gotten wise. The parents and grandparents are people like me who have been through all that shit, so we are under no illusions about the police.

SFJ: The police in London still don’t carry guns, do they?

LKJ: No, they don't.

SFJ: Were you guys talking about Palestine back in the Seventies?

LKJ: Palestine? I don't know. I don't think so. But we would've been in solidarity with the Palestinian people anyway, because we are coming from anti-colonial, anti-imperialist, that was our politics. So our politics would've definitely included solidarity with the Palestinian people. Yeah, sure. It's astonishing though, that the world is just, it's allowed to happen. It’s allowed to happen in this supposedly rule-based liberal order that emerged after the Second World War with the formation of the United Nations.

SFJ: The cover of Dread Beat an' Blood, you're standing outside and it looks like a protest.

LKJ: That was an actual protest. It was part of the George Lindo campaign.

SFJ: Do you think your poem for Lindo had something to do with his early release?

LKJ: I would’ve liked to think that it was a contribution to the campaign, but it was the work of the George Lindo Action Committee and the lawyers. We had some very good lawyers. Radical. We had some very good radical white left-wing lawyers who were willing to stand up to the judges in the court. People like the late Ian McDonald, great, great lawyer. Gareth Pierce, great lawyer.

SFJ: Lindo was only in for about a year, right?

LKJ: Something like that. Over a year, I think.

SFJ: But he ended up dying really young.

LKJ: He died young. I think he had cancer.