writing about 2024

Mary Turfah: Have somewhat embarrassingly kept a diary since high school. I was flipping through this year and a lot of my entries start with some iteration of I’m tired, which is true. I think about Gaza and Lebanon all the time. I’ve been wondering whether there really is a meaningful collective called “humanity.” Like, biologically, genetically, yes, sure, obviously. Still, I look at most people around me and don’t recognize anything at all. Alienation’s the big feeling of 2024, I’d say. Surgery residency has some to do with the fatigue; most of it is the soullessness of life here. I don’t really know what people are living for, beyond themselves. A shrunken existence. (As you would say, brother ew.) The contrast between my life as a doctor here and that of a doctor in Gaza or in southern Lebanon, unravels me. Was in the jnoob a couple of weeks ago, in early December, and found it clarifying. I stood around the remains of my parents’ home and felt something like gratitude, which is absurd. Someone had planted a flag with a Husseini slogan (basically, a commitment to fighting injustice, whatever the cost). There are so many people fighting with the whole of themselves for a better world they might not live to see. I was talking to my dad the other day, I think after I learned the Israelis had shot an old woman in her home, three weeks into a ceasefire only they have violated (1,100 times as of this writing), and I said something like, “this world is awful.” He was eating pumpkin seeds and sipping tea. He looked up at me and said, no, their world is awful. Our world is not, our world is [a bunch of words that sound less floaty in Arabic]. He’s right. Our world is beautiful; may 2025 bring us closer to it.

Cuthwulf Eileen Myles: Never seen America more nakedly in support of ethnic cleansing while acting like girls I once met when I was a substitute gym teacher in Boston in the 70s. One girl would be standing there with a lit cigarette and when I said put that cigarette out the girl would pass it to the next girl and go I'm not smoking. Their defiance was to pretend it wasn't happening and that's how every little meeting with the white house press secretaries go. We’re looking into it. Israel is going to get back to us on that. Meanwhile people are being blown to shreds, kids are being shot in the heart and the head. And now go ahead, why not take Syria. The US is treating the middle east like it’s its bitch and Israel is its cocky boyfriend that can get away with anything he wants. You know what, otherwise, well not otherwise, but in the exact same time and that's the obscenity of the year I just lived, I mostly lived in Texas except when I travelled and the most marvellous place I travelled to without a doubt is Mexico. Mexico gets it. That’s just the fact. Make America Mexico again is what we say down here. I worked on a novel and my favorite public art moment was playing in Bang on a Can with Ryan Sawyer and Steve Gunn who are such marvelous brilliant musicians and friends and I spouted some poetry, some mine, some Palestinian poets, some Polish female poets whose work I had encountered while sitting in my car reading them, the night before the eclipse. We (myself and Ryan and Steve) opened for Deerhoof at Bang on a Can (and I am a huge fan of Deerhoof) and Greg Saunier really liked our sound I believe and referred to us as the Eileen Myles trio. I think we all thought that was funny. Hope so. Otherwise I began referring to myself as Cuthwulf Eileen Myles especially after Donald Trump got elected.

Maya Binyam: Began the year confused. By March I thought I had everything figured out. Life was horrible but it was easy. Someone else cooked all my meals and even did the dishes. I was supposed to be writing. Instead I got high, I got high and thought I saw my ex walk through my bedroom door. It wasn’t sad. It was actually pretty interesting. I drove away after that. I drove through the mountains, the desert, and all along the coast. My brakes needed replacing but I didn’t replace them, I kept going. Summer was coming. Summer got erased by fall. By fall, everything was upside down. On the anniversary of my cousin’s death I taught a story about a man who finds his ex-girlfriend's body in her bedroom. He bathes her in his cologne and then chain smokes cigarettes. My students didn’t understand why he did what he did. I told them he was struggling with time, that time was everywhere, and it was thickening. Attempts at clarification made life more obscure. The failure was collective but on most days it felt personal, it felt like failure was a phenomenon that had originated within me. I tried to put a positive spin on the situation. I tried to believe that failure could initiate its opposite, that it could circle back around and make life more clarifying. John Berger once wrote something like that. When I searched my library, I failed to find the quote.

Jennifer Soong: I increasingly burdened my poems with sustaining me, which naturally caused a number of complications. I lived a whole year in Colorado. Two things that were constant: my jaw pain and the effects of political violence.

Dylan Saba: To be honest, I don’t know that I have something meaningful to say here. This has been the worst year I have ever experienced personally and witnessed for the world, for all the reasons that are obvious. I expect next year to be as bad. Hopefully not worse, but who’s to say.

Nour Ammari: 12/26/2024: Another Christmas in Jordan, and once again, the celebration feels misplaced. Not even misplaced. There is no celebration. This past year has stretched on in a way that feels almost like the slow crawl of tectonic plates. Without the gift of hindsight, it could seem as though nothing has changed at all, but I know that’s not the case.

Of course, there’s a certain privilege in being able to feel that time is so drawn-out. Yes, I’ve faced my own struggles this year, but in the grand scope of suffering, my worst experiences pale in comparison to what Palestinians, Lebanese, Syrians, Sudanese, Yemenis, Congolese—along with my queer and POC siblings—are enduring. Guilt is a paralyzing emotion, and so I refuse to allow it to keep me from acknowledging my own pain, as long as it doesn’t prevent me from contributing to the collective struggle for liberation in my own way.

That said, I can’t shake the feeling of being stuck—we all seem to be. We lift up heroes like Luigi Mangione (a highlight of 2024), the Stop Cop City movement, and the Palestinian activists on the frontlines. We uplift the resistance and necessarily support violence. But somehow, it feels as though the movement is suffocating under the weight of infighting. Every time the opportunity for true escalation arises, some of our own comrades attack. They claim that it will harm the movement, turning away from us just when we need solidarity most.

This needs to change. And honestly, I’m at a loss—because if this continues, we’ll remain stuck in this endless loop of painting our ideals in bright colors, but achieving little in the way of real change. Perhaps these acts of bravery are best carried out alone, though they would be much safer and comfortable with the support of community. Perhaps those who truly act feel a stronger sense of personal responsibility than they do loyalty to the movement. But as long as true escalation is seen as radical and not necessary by our peers, I am not sure where we go. I guess we will find out. I am sick of hearing “escalate,” though. The call to arms has lost its meaning. We either have to do it or not.

As I close out 2024, I’m left feeling like I wasn’t brave enough, that I didn’t have the strength to break away from the confines of what the broader left deems acceptable. We call for action, for escalation, but as soon as the reality of it presents itself, self-doubt creeps in, and the fear of alienating our comrades reemerges.

In 2025, I hope to be less of a coward. I hope to stand firm in my convictions and to no longer shrink in the face of risk or the fear of being judged as reckless.

Chloe Watlington: I get crazy with the commercial-free classical music station. I turn it on before I make coffee in the morning and silence it after I shut off the last light for the evening. I like to toggle the transmitter button a little so that the news or Christian radio breaks through Beethoven fugueing. I like to put on Bobby Womack’s “California Dreaming” and not turn off the commercial-free classical music station. Oooohhh yeah: doubling. The other day RZA was the host of Classical Californian night. He was telling the story of the Buddha who travelled so far to see the monks that by the time he got there he was covered in dirt. The monks said that they are sacred, that they don’t deal with muddy things or muddy people. The Buddha laughed at them. Don’t they know lotus flowers grow out of the mud? Yeah, okay, it's a story we all know, but RZA wrote a whole symphony about it called Ballet through the Mud. I recommend listening to it. That’s what I have been doing all year: balleting through the mud, reading through the mud, talking through the mud. I’m gonna stay right here in the mud, blooming like a fucking lotus flower to the moon baby. See you on the muddy side, if you want. Xoxo.

Hedi El Kholti: For me 2024 will always be the year Gary died. The way 2016 was Bill's, 2018 was Adam’s, and 2021’s was Sylvère. The ones who profoundly shaped my thinking, who made me who I am. I met Gary in early 2000s through one of my teachers, John Boskovich, who had just made a beautiful film of Gary reading Celine’s North. Our lunch at John's incredible place was not particularly pleasant but Gary had just reviewed It’s a Man’s World, a book of ‘50s garish men adventure covers I had coedited for Feral House, so we talked about that. Later Gary and I worked on Last Seen Entering the Biltmore around 2008, but we really became dear friends after I instigated at his request an art show in LA and a symposium on his work at 356 Mission in 2015 to coincide with the reissue of Resentment, the first book of the crime trilogy. Thank you Laura and Wendy for saying yes and thank you Ethan for making it so easy and pleasant. Gary fell in love with LA all over again, and later Cayal who was our assistant at the time found him an apartment. Here, we had a great time. We went to events, dinners, movies, the beach… etc. He came to Colm’s 60th birthday in Dublin and after that we went to my mother’s house in Spain. They got along beautifully. I found a photo of both of them dancing that is super special, but painful to look at.

Last September, we had a beautiful week in Los Angeles, where he stayed with me for a couple of days and later, came every day to swim, hang out, read Balzac by the pool for a project he had in Paris. We talked about our favorite character, Vautrin, who appears in various books in the series. We talked about Gombrowicz’s Diary and the novel he was working on. And as usual when he stayed here, he's grabbed whatever books and galleys that were lying around. This time it was two of our fall releases, Kevin’s Selected Amazon Reviews and Nate’s Ripcord. Gary, with Bruce, Wayne, Chris (for the French books we publish), and Christine, are my first ideal readers, the ones I’m in conversation with, with whom I want to share the books with as soon as they’re done, hoping they’ll approve. With Gary in particular it could be stressful. I wanted him to approve of what I do with the press. I was lucky that he was always very enthusiastic, but I also knew it could have gone either way. He was a pure spirit, unable to bullshit about something he didn't care for. He wrote to me about both lovingly with that intelligence of his that goes right through the heart of what matters in culture:

“I’m bowled over by Kevin’s book, which, with Hamrah’s oeuvre, really should put the practice of reviewing in a certain way out of business, his approach is so free absent the usual judgment-passing, so fluent in tagging what’s important or intriguingly unimportant about a work of art or an electronic toothbrush, and whisperingly gay at times when it’s hilarious in a fluttery, veiled way, that he knocks over a whole house of cards with the veil. I’m very energized by Nate Lippens new book. I loved the first one and also love this one. There are so many gorgeous places in it where abjection meets with resistance from a very powerful writer and someone whose will is getting him through very knotty times without losing his sense of humor, which is—apropos the Tuesday Weld anecdote—devastatingly down-to-earth. Maybe the abject side of it is its power, that behind all that happens to the narrator gets received by someone who can actually stand up to anything, who might very well ask himself, when he’s having a good time, why he’s having a good time, but isn’t going to let the question ruin the fun he’s having, or does let it ruin it, I think what’s so special about this book is that Nate catches the flow of time through an uneasy consciousness, provides an abundance of cues, routines, remembrances, and space bulletins from outside, I love the marking-up he makes of experiences without grading them, so to say, and the contents of Ripcord are so beautifully orchestrated, a little of this, a little more of that, or a little less…the balance is really miraculous, for me, anyway, as I pick up this book, or sometimes Constance’s Playboy, and read a few pages simply to remind myself, “Yes, this is world you live in, and these are some other minds that are working away at not exactly figuring it out and not necessary enduring it as some harsh condition,” but more nosing around for the invisible through-line, if this makes sense, in the seemingly aleatory, the seemingly random. I can’t say enough about how good Nate Lippens’s books are, how glad I am that you’re publishing them. (And glad that you’re publishing mine, truly, forever grateful.)”

I’ll leave you with this 2013 version of Bowie’s “Sound and Vision.” Gary loved Low. Bruce told me it was his favorite Bowie album. For us who made a home in culture: “Blue, blue, electric blue / That's the colour of my room / Where I will live / Blue, blue / Pale blinds drawn all day Nothing to do, nothing to say / Blue, blue / I will sit right down / Waiting for the gift of sound and vision / And I will sing…”

And Gary was a wonderful singer too.

Yasmina Price: No voice was in my head more than the voice of June Jordan, in fragments as litanies:

When we get the monsters off our backs all of us may want to run in very different directions. — “Report from the Bahamas, 1982”

That premonition lives alongside the monsters still being on our backs, now is their time, again. Confronted with the militarization of all things, the commercialization of all things, a state of permanent warfare that is daily and continuous and levelled against any life at all, that is predicated on totalizing disposability, a war zone that is everywhere, that is the architecture of the world we unevenly share, pretenses of democracy that are themselves the ceaseless war war war, a forever war through monopolies of coercive power and conquest and accumulation and intentionally assigned precarity.

In a way that is completely banal and a little particular, I’m not certain to have quite made it through this one. Maybe this was the worst one, disfigured by betrayal and loss.

And yet experiments in liberation endure, somewhere of everywhere elastic models of sustaining life are remembered, sometimes you break bread with friends and family and speak for hours and hours and hours, committing to an ambivalent and contradictory and necessary interdependence is worthwhile and because the commons is not a shape or a place or an end but a process a window is open.

Too much has gone to pieces and still June Jordan also wrote, in “Poem Number Two on Bell’s Theorem, or The New Physicality of Long Distance Love,”

There is no chance that we will fall apart

There is no chance

There are no parts.

Marianela D’Aprile: CHAOS!

Gabe Winant: I’m writing this within the bounds of a nap of our baby, Ermias, now five months old. Will the nap last long enough to get to the end of this paragraph, maybe start another? We’ll see—we're lucky to get past half an hour. He's named after Jeremiah (as rendered in Amharic), the prophet who warned his people that their arrogance and complacency would destroy them; who told the truth even when none would hear it. The Book of Jeremiah is likely the source of the anthem of the labor and civil rights anthem, “We Shall Not Be Moved”: “Blessed is he who trusts in the LORD, Whose trust is the LORD alone. He shall be like a tree planted by waters, Sending forth its roots by a stream: It does not sense the coming of heat, Its leaves are ever fresh; It has no care in a year of drought, It does not cease to yield fruit.”

We stopped singing him lullabies as part of sleep training, but when we still were I found that, while the traditionals of social movements like “We Shall Not Be Moved” featured heavily in my repertoire, I couldn't stop singing John Prine's “Paradise.” You might think it's called “Muhlenberg County,” as I used to: “Daddy, won't you take me back to Muhlenberg County / Down by the Green River, where Paradise lay? / Well I'm sorry, my son, but you're too late in asking / Mr. Peabody’s coal train has hauled it away.” The third verse is where Prine nails the ecological point: “Well the coal company came, with the world's largest shovel / and they tortured the timber and tore up the land / they dug for their coal ‘til the land was forsaken / and wrote it all down as the progress of man.”

At first, I thought I was doing this because of the genocide in Gaza and its ramifications for academic freedom and academic labor, questions with which I’m very actively engaged. Muhlenberg College (unrelated to the county, but their namesakes were related to each other) in Pennsylvania made a landmark this year by firing Maura Finkelstein, a tenured (and Jewish) professor of anthropology for her social media posts about the genocide in Gaza. It is, I believe, the first time a tenured professor has been outright fired for Palestine solidarity, although there are previous cases that were de facto the same thing. Every time I thought about repression on campus, as I do constantly, John Prine started playing in my head. Then, months into this, I realized—it’s a song about a father and a son, and the irretrievability of a past from which they have been severed by the violence of fossil capital. Okay, he’s awake.

Rosie Stockton: This was a year I did not know when to hold em or when to fold em. When I finally walked away, I watched all of The Sopranos in my best friend’s living room. That’s a lie. I stopped when Tony didn’t stop Ralph from putting the hit on Jackie Jr. After Tracee and everything. Could not forgive him for that. It was then I retaught myself how to breathe. Where the air goes, how to make room for it. The simplest form of pleasure, turning the bottom of an exhale to an inhale. I architected solutions in time and space. I slept in a twin bed. Paid rent. Wrote in a yellow notebook on a glass desk I bought from a 12-year-old on Craigslist for 10 bucks. As I slowly loosened my grip, I studied how my palms had warped the metal. I craved soft things. Cashmere. Hojicha. 105.1. At the hands of myself, I experienced deliverance, having never before wanted to be free. Once I felt it, I sat on the floor for a very long time. I walked on a dirt road for a very long time. Everything I tried to bury I gathered back in my arms. At the opera I yelled to Romeo please just take it slow, it’s going to be okay. But still it wasn’t okay. I read Capital Vol. 1 on a dock in Maine with a broken heart. That worked. Commodities are in love with money, but the course of true love never did run smooth. Disavowing Anna, I entered my Levin era. Gardened. The scythe mowed of itself. These were blissful moments. Filled barricades with water and daisy chained chicken wire to itself. Set up tents. The cops came. Locked arms with undergrads and whoever else. Ran each day alongside the LA River, fast as I could. Felt the moon crack open the sky. Looked east until I realized I could get there by looking west too. All the poets are in Palestine. Words’ only job is to point to what isn’t. I made peace with the fact that speech hurts. It hurts my mouth, it hurts my throat. It hurts my joints, my jaw. My stamen and my pistil. Once I grieved in every dimension, the future finally ceased to exist. That was a huge accomplishment. Enough, I said to my analyst. I am cured. I know how The Sopranos ends, I don’t need to see it. He said perhaps our work is only just beginning.

Nour Annan: I knew the war was coming and there was nothing I could do to stop it. I told everyone who would listen, like a hysterical town crier, desperate for the world to acknowledge the doom growing inside of me. It arrived in September, tearing everything in its way, erasing all that we had known. As with Gaza, we helplessly watched it on our screens. We watched as the zionist army killed and displaced our kin, as they destroyed our land, burned our trees. As expected, I became even more addicted to following the news, inseparable from the screens that delivered a play-by-play of my greatest fears. When my madness heightened, I booked a plane ticket to surprise my family in Lebanon. It was November by then. When I walked into the apartment, the cat was hiding under the bed and my mother was praying. She began to cry upon seeing me, whispering thanks.

Although the drones and bombs interrupted all of our waking and sleeping hours, I felt calmer and stronger than I had in New York. A grief like this is not meant to be solitary. There were 14 of us in the Beirut apartment, and we lived out the remainder of the war together, breaking bread and bad news, smoking on the balcony, waiting for it to end. The night before the ceasefire, the skies closed in on us. I remember walking home along the corniche in a daze while people fled in all directions, piling bags and bedding onto motorcycles, running to the beach in a panic. The air smelled like gunpowder. That night, at home with my family, we heard the bombs drop all around us, the planes hovering, encircling the city, cracking the sky open. A feeling of gratitude washed over me, to be here and not there. If anything were to happen, I would be here, with them, I would die here, with them. It was 4AM when everything stopped. The sigh of relief, the tears of disbelief, the shame of resting before Gaza, the fear of what is to come when the dust finally settles. There are years that get stuck in your throat forever.

dream hampton: Ugh, what a bleak 15 months.

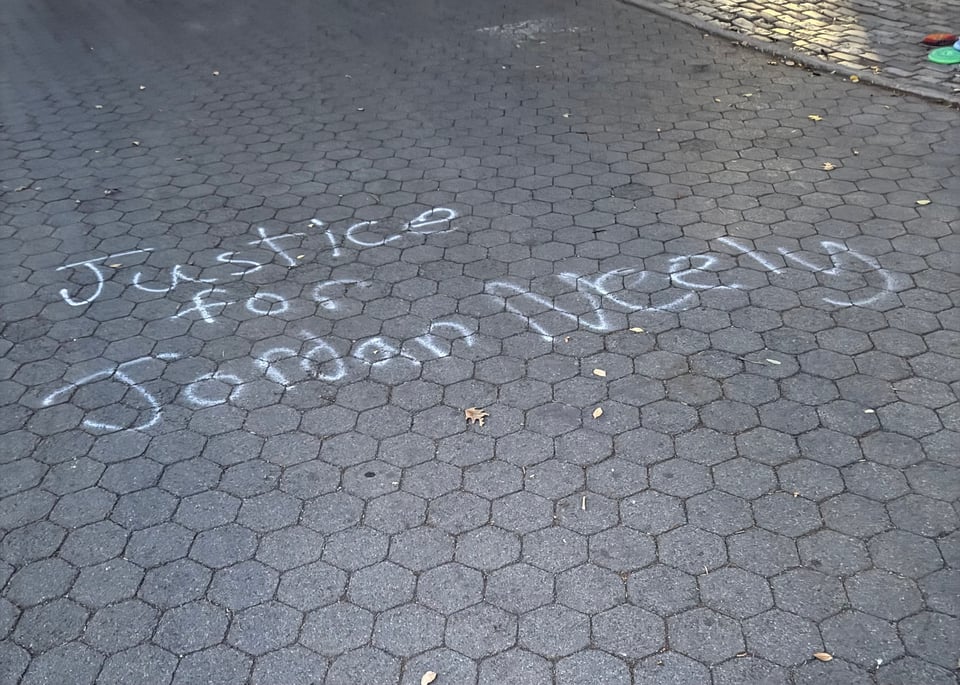

Eli Coplan: 2024 began for me when I missed my best friend’s birthday to help block a bridge. We (some of us here?) spent the night in jail and I got doxxed by the Post, Google results inscribed into my name like getting tattooed by the Internet, except that mine will look better with age. This was at a time in Palestine organizing that feels distant now despite having been met with no end. Art was unthinkable and I met a lot of people without learning their last names. I met Sasha in the bunker. The process was the opposite of art but we were thinking in terms of meaning and circumstance and it was, selfishly, enlivening amidst all the despair and guilt. Everyone was looking to the past for techniques to break something in the present.

The year before, I had made a sculpture of a car horn that consisted of a real car horn, connected to a DC power supply and controlled by a steering wheel mounted on the wall. The horn apparatus needed to be deployable so that I could install it on the outside of a north-facing window eight stories high on the old Whitney Independent Study Program building in TriBeCa on the morning of the opening, because permission is a gift best given retroactively. I’m convinced that it affected traffic in the surrounding area.

Perhaps auspiciously then, 2024 became for me a year of traffic, of frustrated desire and slowed movements with the occasional saccadic twitch forward. Keeping up with the present feels like running in a dream, and maybe that’s why I ended up writing about 2023 just now. Eventually I did get back to making artwork but I decided I could only do so if I didn’t take it all that seriously anymore but also made no compromises. It did sort of end up with me spinning out, brain and thumbs clogged with dopamine and I still haven’t caught up on emails or even texts now. I was lucky for the opportunity to withhold image rights from Penske’s Artforum but I wish that doing so had felt more like an achievement. It was the year I came to understand that it is, actually, traffic that controls the world. This is the first thing I’ve written all year.

Andreas Petrossiants: Currently, the NYU Department of Photography and Imaging is exhibiting a show called “BREAD • EDUCATION • FREEDOM - 50 YEARS LATER.” Approaching on Broadway, it begins with a blown-up photograph visible through the storefront windows. In a beautiful floor-to-ceiling celebration of militant urban assembly and autonomous action, the photos document the revolutionary events in 1973 Athens when “surrounding Universities went on strike and began occupying the Polytechnic in opposition to the military junta that had been plaguing the country since 1967.” It’s ironic, to put it mildly. NYU is a vehicle of investment, it’s a tool of gentrification and urbanization, it’s an arm of the surveillance and police apparatuses, it’s its own kind of junta. NYU lets the cops use the bathrooms at the library and invites them to bludgeon students and faculty in between candy crush breaks. NYU has built literal checkpoints across campus (blocking off spaces that are ostensibly open to the public), staffing them with subcontracted security guards working taxing shifts. Students active in the struggle to end the genocide in Palestine across the US and the globally have underlined the greatest myth to the contemporary neoliberal university: that it is still primarily a space for learning and collaboration rather than one of numerous technologies for the production of debt, speculation, and urban development. In December, NYU declared faculty members and students personae non grata (PNGs) for participating in a peaceful protest. May we all be unwelcome. May we all be ungrateful.

Danielle Carr: This year was a referendum on integrity. It was immensely disappointing.

Sunny Iyer: I started the year on the beach in Kerala with new friends—almost strangers—full of crab curry and fermented palm wine (toddy). I remember the distinct feeling of being on the other side of the world. I remember feeling hope that Israel would fall, that change would come. I spent the first week of the new year with my grandma, whose senility and lack of English meant I never really knew her, apart from a few scattered fond memories, like the time she visited my northern California suburb, went for a walk, got lost, and while I was driving home from high school, stoned numb blasting Black Dice, I found her crying on the sidewalk, so relieved to have been inadvertently found. In April, my mother was one day away from reaching Mount Everest base camp when we finally got a hold of “her” sherpa on LinkedIn so that he could pass along the message that my grandma died. She chose to leave her trip, something she’d been planning for years, and took a helicopter from a mountain village to Kathmandu then a flight to Kerala in time for the funeral. She still regrets making this decision. She could have said goodbye to her mother 17,500 feet above sea level, in the wind of the tallest mountain on earth. This year has been categorically defined by grief and rage; the world is all caved in. I’ve lost friends and family by way of death, political difference, misaligned schedules, geographic distance turning into sedimented emotional divergence. I’ve grown resilient in parallel to a heightened awareness of precarity. There are few things I know to be true, one of which is that all the even years of my life have been miserable, and the odd years elastic and profound, so I’m ready for this last stretch of my 20s.

Dave Tompkins: Back in May, a friend in London played “Hold Tight” by Change, listening for Luther Vandross in the refrain. The chorus found me again last week, stilled in the woods of Western N.C. and considering a tree shimmy, as ten wild hogs filed across the path. (Luckily, their snuffle ops did not include me.) The song has appeared in my head so often, in a year of people being forced to hold and carry too much, that it spilled onto Curtis Mayfield’s porch in Atlanta. A dream in a waking nightmare. Curtis was talking, maybe arguing, in a reread of the title’s multiple embraces. A hug to self? A clenched anxiety? Stay put, but wait for how long? Was help ever on the way? At one point “don’t let this moment” cuts off, as if in resistance, leaving us to it. A call to bring your people close, he said. Mr. Mayfield then waved me out of my own dream (I asked if he’d written “Song for a Future Generation”) and scoffed, “Wrong county!” The Change single often makes brief cameos in my favorite record shop (shout to Bene) which also holds my favorite book shop. (And an award-winning bathroom.) Located at 360 Van Brunt in Red Hook, the shelves in the right hand corner include Palestinian authors—literature, poetry, history, children’s books, cookbooks, all populated by Sousan Hammad. There's a worn leather chair where you sink in and listen to the records of others. Or, one time, hear two kids singing New Edition's "Is This the End?" while strumming on an acoustic guitar, off key, voices cracking themselves up. Or read Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear by Mosab Abu Toha. Or if needed, just sit tight.

Naib Mian: If 2023 showed us possibility, the briefest glimpse of liberatory potential, a tear in a fence, a prison break; then 2024 showed us the cost. 2024 showed us that the greatest might on this earth would be unleashed by those with the greatest hubris to eradicate that possibility. Hope is to be met with bombs, and dissent is to be made untenable. But it also showed us the power of that possibility. That in the face of the greatest horrors known to man, the flame of possibility in Gaza could not be put out, and that flame could ignite a movement around the world.

This year was a reorientation. A few months into Israel’s accelerated genocide in Gaza backed by the United States, we entered the year mobilizing, organizing, reacting.

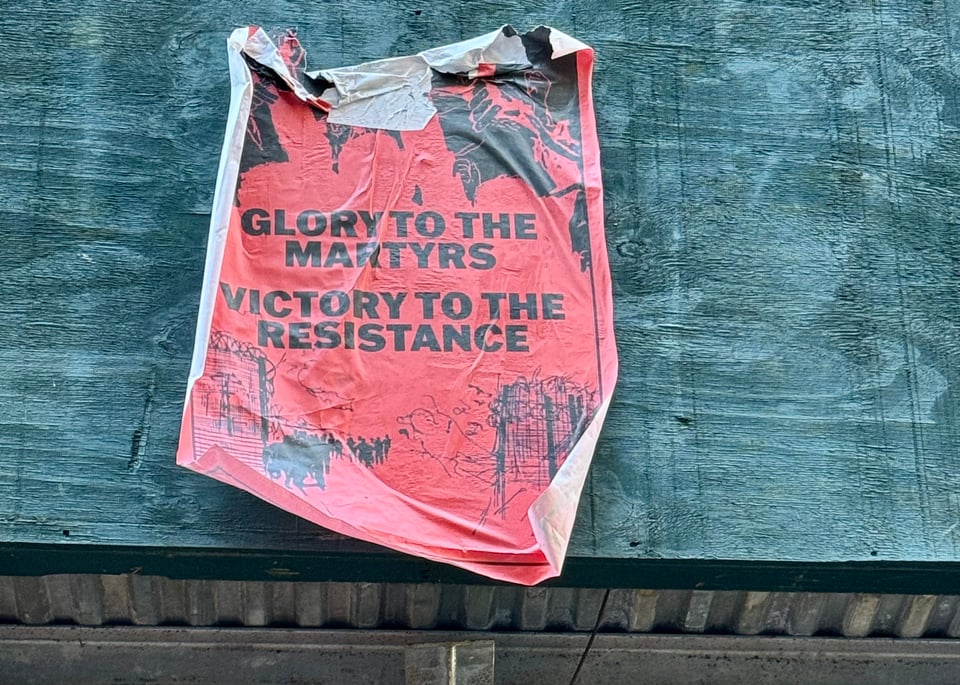

It’s astounding to reflect on it all. Hundreds of thousands in the streets around the world; uncountable ceasefire resolutions; expanding consumer and cultural boycotts; bringing streets, parades, train stations to a halt; genocide cases in international courts; targeted actions against arms manufacturers; port workers heeding calls to withhold their labor from the global transport systems that get the weapons of war into the hands of genocidaires; student encampments spreading like wildfire across the world with a unified call: disclose and divest.

And equally horrifying was the effect of it all—nothing. The bombs did not stop. The genocide did not end. The death count has not stopped rising. And the horrors we’ve borne witness to, broadcasted to us by the journalists on the ground (heroic doesn’t begin to capture what these individuals have had to weather to tell their stories), have only grown darker and more twisted. Every functioning hospital bombed, besieged, or burned; aid trucks targeted; more than 200 journalists killed; genocidal thirst expanding into Lebanon, Syria, the West Bank. We won’t forget the writing on the walls, the faces of the children. I don’t think any single piece of writing can outline it all. We’ve seen worse than the worst we could imagine, and it doesn’t stop.

But we’ve also seen resistance and resilience. The brave fighters in Lebanon who staved off Israeli expansion. The image of Sinwar fighting to his last breath. Nothing can forgive the horrors brought upon the Palestinian people that they have responded to with principled steadfastness and the struggle for life. Palestine is the blueprint for liberation.

Here at home—in the heart of empire, where the bombs are made, the checks written, the red lines erased, the green lights given—as the year progressed, as we reacted to the gravest horrors of our time, we also saw counterinsurgent forces make inroads into the movement. Forces that would see calls for material divestment channeled into the neoliberal bureaucracy of trustee committees or righteous anger channeled into electoral voting blocs for a genocidal “lesser evil.” A multiplicity of tactics is necessary for a movement, but it cannot become cover for cooptation. The horizon of liberation that we struggle toward is not ours to compromise.

To the culture workers among us—the writers, artists, filmmakers, and all of us whose labor manufactures culture and shapes minds and hearts: we must sharpen our analyses, agitate our audiences, and resist the counterinsurgent forces that use culture to maintain genocidal consent. Culture cannot exist merely for consumption; it must move us into action. It is our responsibility to disrupt any and all counterrevolutionary culture, and any alternative cannot recreate the exploitative, capitalist modes of pre-existing cultural production.

As we turn the page on another calendar year of genocide, my mind goes back to Fargo Tbakhi’s words in his “Notes on Craft” about the long-middle of revolution:

The long middle is not a condition of time; we might be nearer to the end of revolution than the beginning, we might be nearer liberation than defeat, but our experience and our actions exist within the frame we can see, the frame of the long middle. Liberation is the end…We move towards it— sometimes slowly, sometimes quickly, but always. It is the location by which we orient our movement. We know it because it gets closer, not necessarily because it comes sooner.

We’ve mobilized, we’ve tried to raise the stakes, we’ve pulled on the levers we have access to. Yet liberation remains on the horizon. And from our position in this long struggle, we look back, we look forward, and it is impossible to say whether we’ve made any progress toward it. But such is this long middle. So what now? The struggle to continue is the one I've come up against most often, myself and with my comrades. But it's understanding the long middle that allows me to.

The long middle, then, is the affective experience of moving inside the dailiness, inside the structural and therefore constant violence that forms the machinery of genocide and greases its wheels. Yet this affective experience also is, or might be, one of a counter and opposing dailiness: the dailiness of resistance and unrelenting struggle. This counter-dailiness is modeled by Palestinians, whose struggle within the long middle takes an astonishing diversity of forms—forms of care, of tenderness, of violence, of ingenuity, resource, and survival.

The long middle is not a geography of stasis or relenting. Accepting it means bringing our bodies into a state of movement and action, into a state of daily struggle. And if we commit ourselves to that, then we also need to organize. We need to build capacity and structures of sustainability. We need to expand the movement. We need strong, healthy organizations; we need political education and discipline; we need structures of mutual support; we need to hold one another accountable; we need to recruit; we need to build tactical skills.

This constant Intifada is the path through the long middle. Intifada is a shaking off of oppression, shaking it off like a layer of dust. This is a bodily action, to shake, to convulse oneself in a constant motion of refusal, to be clean in the face of the world. We will get tired. Our muscles will tear, and then get stronger. Someone falls, we pick them up. We fall, we are lifted by others. We must continue.

We won’t know when we will reach, but we keep moving, we keep fighting, we keep struggling. Such was the reorientation of this last year. A reorientation toward the horizon. That no other direction, no other orientation, no other way of existing in this world is worthwhile or makes sense other than struggle toward liberation. We are in this for the long haul. That doesn’t mean slowing down. It means maintaining the daily struggle to speed up.

Free Palestine.

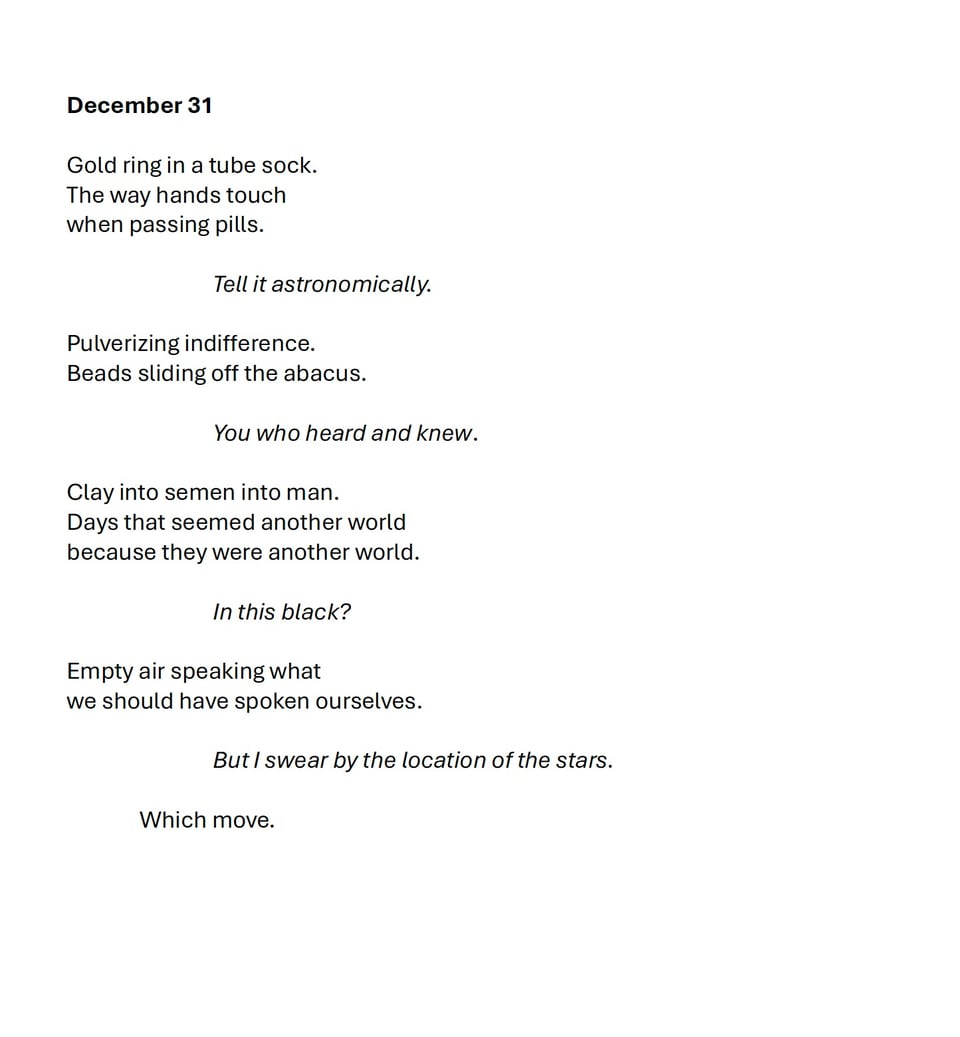

Kaveh Akbar:

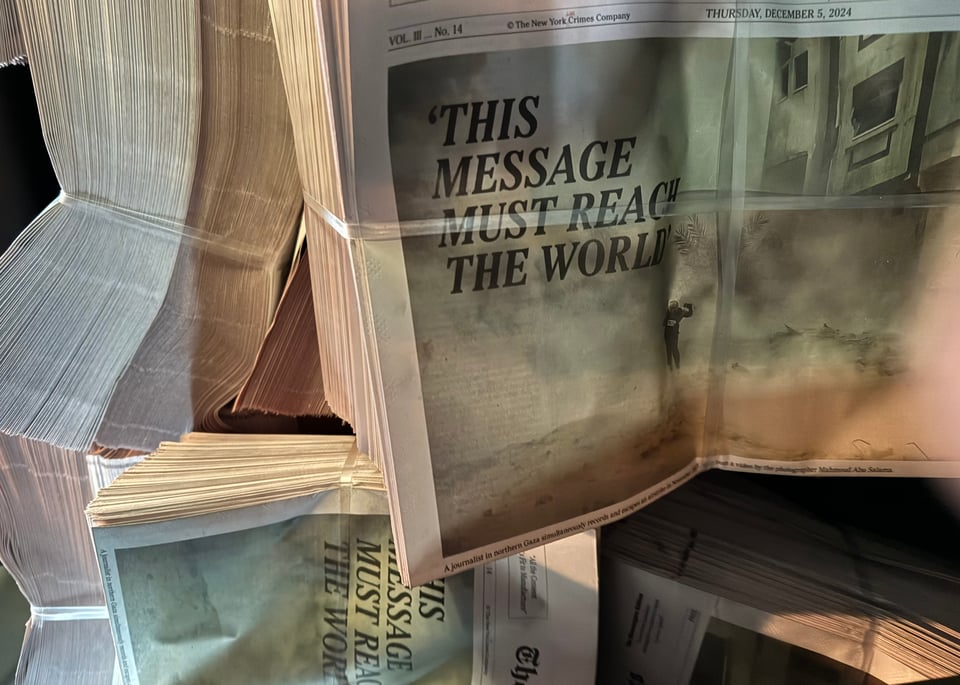

Sarah Schulman: Every brutal impulse that we ever suspected or ascribed to the United States has come to the surface this year—starting with Biden’s endless influx of funds to the Israel butchering of Palestinians and ending with the election of a fascist and the shift into the new era of American Right Wing anarchy and chaos. Arts and Entertainment played a significant role in undermining Democracy by stuffing our faces with repetition and narrowing, profoundly, the tiny range of ideas available in the public realm. The deliberate descent of The New York Times into a rag has made it almost impossible for Americans to access information without digging through multiple obscure sources and trying to piece it all together. The greatest danger now is appeasement.

A.J. Daulerio: 2024 was a wonderful year, but now I second-guess that as I type this out. Was it? 2023 was difficult, but I was exhilarated by what felt like max-cap frustration and disorientation; therefore, I declared it an outstanding year, mainly because I work better from a place of scarcity and nihilism. Then, this year was month after month of wins. Many were small and surprising, but there were several that a former version of myself would have considered “lifelong dreams that had come true.” After they came true, I realized that those dreams were kinda dumb, though. Like, “Why dream so big, man??? Just live like a normal fatso beast, go to bed, and see what tomorrow brings.” Maybe that’s why I'm so tepid about 2024 now. But calling my shot—in 2025, I will try to wish less and accept the terror of it all.

Nina Renata Aron: For me, 2024 was a year of rage and grief. It was also a year in which everything seemed connected: all rages and all griefs; grammar school boys pushing each other outside my window and the death-by-missile of a Palestinian poet; Matt Gaetz’s face and the trial of 51 French rapists who thought they’d done nothing wrong; city-destroying floods and a new skirt. It is no longer necessary to pull apart the various threads. It’s all one disaster.

The marquee events were the genocide in Gaza and my father’s decline and death, two distant, seemingly unrelated nightmares that I also experienced as deeply entwined, maybe because I watched the events of October 7th unfold on CNN with my journalist dad as he opined from a wheelchair, or because I railed against the IDF every time we were together until he died.

The horrors in Gaza vanquished the last traces of my naiveté, traces I would have disavowed if someone had accused me of harboring them, but that I had to admit to myself. To be more specific: before this, I think I simply did not believe that Jewish people were capable of cruelty and brutality at this scale. I’ve been an anti-Zionist for a long time and perhaps should not have been surprised. But I was. Watching the violence unfold this year, it became clear, to my great shame, that I actually thought that an army of Jewish boys and girls not much older than my teenage son and daughter would not block aid trucks, shoot toddlers through the skull, drop bombs on refugee tents.

This year disabused me of those last pathetic shreds of exceptionalism, of faith. I heard “nice” Jewish people in my orbit defend this violence, try to explain to me, an American Jew with no family ties to Israel, why I didn’t understand. I saw the banality of evil up close in a couple milquetoast moms I know who parroted whatever bullshit headlines their hawkish husbands had scanned that week, unthinkingly, as Palestinian women screamed over the corpses of their babies on screens for all the world to see. Among so many other things, the whole idiom of Jewish motherhood lost its meaning for me this year.

Death dealt the other decisive blow to any remaining innocence I might have possessed. It brought me low and made me grateful to be alive.

I really enjoyed reading Susie Boyt, Victor Serge, Isabella Hammad, Mark Haber, Venita Blackburn, Dubravka Ugresic, Joanna Hedva, Eva Baltasar, Yuri Herrera, Olga Ravn, Helen Garner, and newsletters by Sarah McColl and Lisa Locascio Nighthawk, among others. I enjoyed listening to Cindy Lee’s Diamond Jubilee. I enjoyed writing group and playing music and cooking and baking and being in love and hanging out with my kids and my sisters and mom and dear friends. And I enjoyed playing and watching as much soccer as possible. I’m still reporting to my dad after every game, although the one-sided conversation now makes me cry. That’s the kind of thing I’d roll my eyes at if I saw it on TV. When I pass the cluster of photos of him on the mantelpiece that even 17 years in California won’t make me call an altar, I say aloud, “I’m trying.”

Ariana Reines: I really enjoyed hanging out with kids in 2024. Kids are the best.

Maryam Tafakory: Growing up in Iran, I heard the phrase “it cannot get worse” more often than the national anthem playing in school every morning. It has been impossible to keep sane in 2024, and before all this, I thought 2022 was the last bullet my body could take before collapsing. For over a year, we’ve witnessed too many people hesitate to call what they could see with their own eyes by its name. For over a year, people have been gaslit into using any word other than what it is: genocide. 88% of all homes have been destroyed, entire families wiped out, yet many chose to stay silent. For over a year, we have faced the ugliness of how we have routinely accepted our complicity. Free Palestine.

Constance Debré: Everything went fine.

Minh Nguyen: It started as an ache in June, but by the height of summer I was in debilitating pain. Society is divided between the sick and well, and I had landed on the other side. Luckily I was in Saigon by August, where I received thorough and caring medical treatment for half of what I would have paid in the US. Before I was properly diagnosed I lived with a bad mystery. For a few weeks I contended with my mortality. Staying at a hospital near my birthplace I thought about the behavior of Pacific salmon, how when they begin to die they swim back to the streams where they were born, decomposing on the way. But I did get better, and even with the scare, I had a good personal year. I got jobs that I genuinely enjoy though that has its own problems. I rejected practicality to spread across three home cities. I became better at organizing my life on my terms, an act that when you don’t come from money can feel like cosmic revenge. These choices come at great costs, but still—it is a privilege to live on one’s terms, to even be able to try. 2025 is for remembering this often.

Melissa Febos: In early December, ice encased our Iowan trees and when the wind bent them, they knocked like an insistent visitor, hello? hello? I was glad to be home after so much traveling. I had finished a book and started another. I'd missed my wife. I missed my dog, though he was gone. I had thought I'd managed not to be hopeful about the election and immediately knew I'd failed. I called everyone I loved and rolled out my life like a map. I wanted to know what else I could do, what a middle-aged sober addict with a bad back and high-maintenance mental health hygiene could do, if there was something better than standing in a room arranging sentences, sitting and trying not to think, strengthening my core, scribbling in notebooks and talking on the phone, walking around my midwestern town, and teaching. There seemed to be some, but not a lot more. I had always talked a lot about love and also spent a lot of time avoiding it. I'd had a lot of thrill and a lot of hurt both seeking and avoiding it. Now I think there are bigger kinds of love, more walk-ins welcome varieties, more applied sorts, the ones you choose again and again. I had talked to other sober addicts and drunks every single day for 21 years and I'd keep doing that. I'd keep arranging these sentences. All the rest, too. How to walk and teach and sleep and eat and stroll the Hy-Vee with the genocide in one hand and my wallet in the other without cracking down the middle? Maybe it was just the ice cracking, not a break but a knock. Hello? Hello? Come inside, come on in.

Anna Shechtman: This year, like every year, I have devoted myself, or at least my time, to my mother. Hours of talk. I’m her correspondent from the classroom and the internet, relaying aesthetic and moral trends, tracing the political horizon as far as I can see it stretching and contracting. Some of the things I tried to explain to her in 2024 include:

A “pick me” isn't like other girls. She eats burgers and watches sports; she spends no time fantasizing about white dresses. She does or doesn’t do these things for male attention and is, essentially, a gender traitor on the heterosexual dating market. Like you! she interrupted, either bad listener or evil genius.

It meant everything to me, really, to hear that she liked my book. It’s a real page turner, she said … I mean, not every page … so I had to remind her what a compliment is.

People are upset that this is only the first time Elphaba has been played by a black woman, leading to some online fuss about whether she or the animals are the vehicle for Wicked's anti-racist allegory. Whatever, Idina Menzel was black enough, she said, running the discourse through a guillotine.

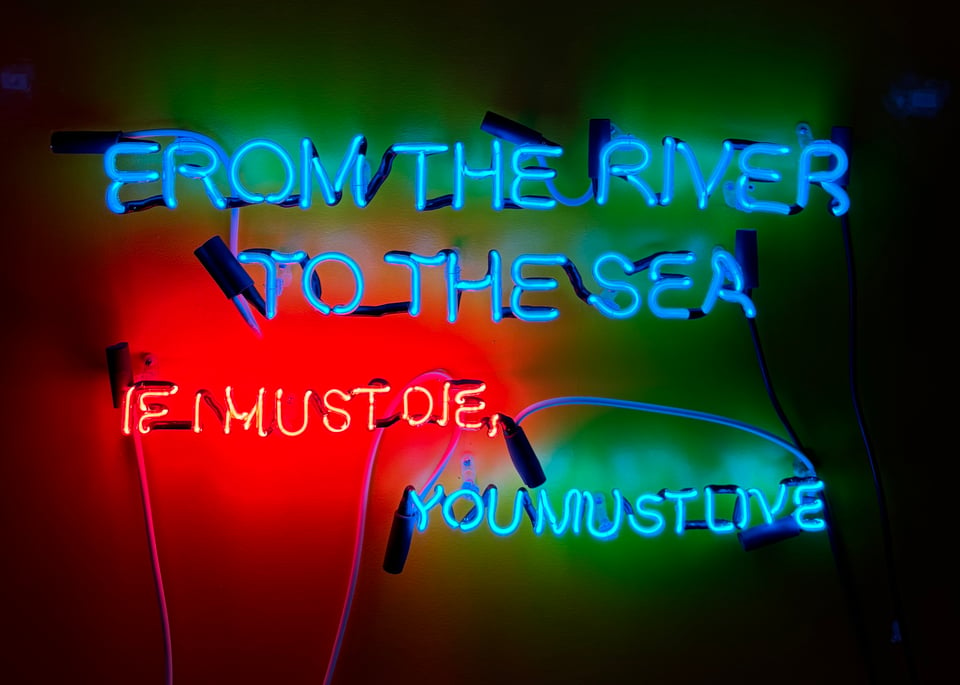

There’s no antisemitism on college campuses. This, she has had no trouble believing, as she has never equated Judaism with Zionism. But as a Jewish child of the 1960s, she doesn’t hear “from the river to the sea” as a cry for Palestinian liberation, only a call for the elimination of the state of Israel. The conversation tends to break down when I inevitably offer: And what if it were that too? …

Isabel Ling: My 2024 began with stress dreams about Streeteasy. My best friend and roommate, who I’d lived with my entire adult life, and I parted ways (amicably). She moved in with her boyfriend of many years, and I, perhaps competitively, also wanting to take an equally big next step across the threshold into adulthood, decided to live alone. I moved deeper into Brooklyn, signing a lease on an apartment I wasn’t sure I could afford. Learning how to live alone has been one thing, being lonely has been another. I talked about my new apartment a lot this year—at bars, at the park, in the pool at the Bed Stuy Y. Stories about my very crooked floors and windows that never fully closed (read: ant infestation), were an architecture for the internal discomfort I felt with this yawn of aloneness. On the other hand, it also pushed me to reach toward others. This year that looked like calling my parents more. Like listening to the student journalists over at WKCR bravely report on the NYPD raid of Hind’s Hall alone in the dark of my kitchen, but then linking with the homies at jail support. Like dancing more. In a strange twist of fate, it’s looking like I’ll have to move out of my apartment in 2025. But, ending the year, I’ve fixed my windows and gotten used to the floors, I love my space and like being alone.

Elena Saavedra Buckley: In early summer the ceiling in my apartment collapsed while a few other bad living situation events were happening simultaneously. I remember talking to my mom on the phone in the aftermath and really thinking that a chain reaction had been set off, and that I would have to move back to Albuquerque, or maybe die, though I didn’t want to. It just seemed possible. Right before all of that, I had broken up with someone whom I wanted to love but couldn’t. He wouldn’t let me, and if he had, I bet I would have realized very quickly that it wasn't right. And then, just after the ceiling, I fell in love with a new person, Chris. (He’s sick on my couch right now, actually. I kissed his head before walking to the train, where I’m writing this.) It was interesting that falling in immediate, potent love coincided with the slow resolution of my other woes, because it proved something about the many faces of fulfillment. I’ve felt precarious for years; no surprise today, when so many are dead who weren’t two years ago and when the black plastic spatula in my kitchen will kill me if I manage to avoid different threats. The safety and happiness that I found this year did not fix that precarity, did not fill knowable gaps, but instead expanded the definition of my life—I marveled at new pleasures and feared new things. Yesterday, for example, when Chris was still feeling gastrointestinally ill, I discovered a new emotion while crying both because I was sad that he was in pain and because I was laughing at his fart performance. Early in our love I sent Chris a picture of a doo-dad that I saw at a Michael’s: a wooden purple cassette that read, LIFE IS A MIXTAPE. Chris then went and found the thing at a different Michael’s and bought it for me. It really is “so true,” that new songs come along and change the old ones, and that the linearity of their order is as overwhelming as the eventual timelessness. LIFE IS A MIXTAPE sits on a shelf in my new apartment.

Jake Romm: Christmas Day walking alone in East Berlin singing Cindy Lee to myself taking pictures of trash: something about the unpresentable (“all I want is you”): unseasonable=unconscionable warmth: on the look out for some kind of shrine=oven. Crow, a friend, on a pile of rubble picking at a white rag=flag and all in the back the dormant machinery and the exposed pipes rusting in a ditch=mass grave: think of what A said about looking at Poussin that the sight=Gaza=is inescapable; I said: it caused the image to say it back. Wandered up the wrong stairs absentminded hounded out by pigs i.e. ACHTUNG state area=Gaza. Hands clasped behind back at the Old Gallery: all the soldiers in the Italian paintings hide their faces in shame and exhaustion when Christ appears; gleaming white St. Michael stabs satan with his spear and gives him the side wound of Christ, Satan’s indignant face pain borne in innocence: how could you? Gelid/saline city/people: the sun is just a semblance of memory: I mean the city=world is a tomb that deserves no light. Finished reading Mayröcker (ach) yesterday she writes 3 words in As mornings and mossgreen: “wolfish” “tumor” “scale”—right: fever sick in bed on new year’s eve, a little delirious/jealous of the fireworks lighting up Neukölln=celebration in a desperate key= sound of the bombs of the past year: rehearsal for the next.

Juliana Halpert: On a late-January lark, a college friend and I went camping, just for a night. We drove two and a half hours from LA to Los Padres National Forest, and hiked an easy mile to the giant sandstone rock formation known as Piedra Blanca. We passed some day hikers and a group of young guys sitting around, smoking bongs with their shirts off. We set up her tent in a sandy niche between several paunchy boulders, with privacy in mind. We draped our sweaty sports bras and dirty socks on knotty shrubs, we made a fire, we compared gear, we cracked up and mulled over the man I’d been seeing. Then we got bundled up and slithered into our bags to sleep pretty early, all talked out and stinking of smoke.

I woke up to my friend nudging me rather forcefully. “Do you hear that?” she asked, full of fear. The age-old camping question. It was pitch-black outside, and I could only see her silhouette. But I did hear it: voices, getting louder, all male, making idle conversation. They belonged to those young guys, and they were headed our way. My friend and I listened, bodies tensed. It was all bro-speak chatter, nonsense, jokes ricocheting in their own private lexicon. They sounded like idiots. They had no idea we were there. “Are all guys this fucking stupid when we’re not around?” I whisper-joked, despite my beating heart. Shhhhhhh, my friend said. To our relief, their voices soon trailed off. I listened to their banter until the sheer silence returned, then shivered myself back to sleep. Almost twelve months later, I can’t for the life of me remember anything those guys said—it’s incidental. But that fly-on-the-wall feeling has stayed stuck to me all year. Witnessing without tampering. Shutting the fuck up. It was pristine. We laid in wait, two secret, silent women of the sand. We were not unlike the mountain lions that, on just about any hike out here, are surely tracking your every move.

Ottessa Moshfegh: 2024 was massive; if I’d seen it coming, I might have run in the other direction. The growing pains have felt like unanesthetized surgery. Nobody close to me died, thank God. I found a few new friends in odd places in the world. I traveled a lot. I went to Spain, Italy, took the Orient Express from Venice to Paris. I turned 43 halfway through the year alone in Brighton, England for the second year in a row. I got to spend time with my nieces in Massachusetts and see my parents. I was asked to be a godmother, which moves me every time I think of it. I lost hope and found some and it ran out so I had to find more. Still looking. Sometimes I feel like my body is being bleached from the inside. I feel I'm able to love more fully than before. I feel like I understand my intention for myself better now, and it's basically to grow into something I’m not yet. I used to intend to be my optimal self. I'm willing to let that idea slowly secede. I see new ways that I’m not perfect and realize that I didn’t appreciate them before. I love the book I’ve been writing and I'm excited to go back to it. I end the year grateful for my husband, my four dogs, my home, my career, and the friends who will forgive me for disappearing from time to time. It's nice that the year is ending. I hope it ends softly.

Piper French: This past January I got an unexpected email that altered my entire year. Nine months later, I flew to the south for a hearing related to the legal case in question, where for a week I sat in court shivering as teams of lawyers debated facts from a morning that occurred decades ago, just a few months before I was born. I couldn’t stop thinking about how we only pay this much attention when something really awful happens. Then, walking back across the bridge to my hotel one afternoon in the oppressive humidity of early fall, I became preoccupied by how imbalanced it felt to scrutinize the past so closely for this one life, when scores of people were being incinerated in a given instant in Gaza and Lebanon, deaths that would never be examined, never adjudicated—deaths that would end up as little more than numbers. (And even the numbers would be in question; the spokesmen of the country that supplied the bombs, my country, would publicly dispute them as the figures of a health organization in thrall to a terrorist group.) This is obviously not an argument against due process, not that due process worked for the guy I was there to write about: All this scrutiny and he had still spent more than half his life in prison. It was simply an overwhelming feeling I had about the rules we make for life and how arbitrary and contingent they can be; about the difference between what power allows under the guise of procedure, and what power does brazenly and dares you to object.

What else: In between January and September, my relatively stable life fell apart. Following the abrupt dissolution of a very long relationship, I felt unmoored; every decision seemed cosmically pointless, which I suppose is more or less the feeling of total freedom. I got into lots of debates about what constitutes due process in this context. I also wandered around New York and Marseille by myself, listened to Street-Legal approximately one thousand times, had a small number of insane encounters, and melted one teakettle for reasons I can’t disclose here. I’m still trying to replace it.

Neeraja Murthy: This year I became a cat mom. I’ve been on notice ever since Pumpkin first stepped paw in my apartment. Every move I make in here has both of our shadows, but I can’t be annoyed because she’s morally correct about everything. I’m no longer able to eat in my own house without having something ready to feed her. It makes so much sense. Eating is a group project. When I pick up any object, she runs over excitedly and I have to let her explore it. It doesn’t matter that the object can’t do anything for her, the fun is in discovering. When I pull all nighters she checks on me constantly, meowing and demanding attention. So true bestie! Deadlines are made up, cuddling is real. I find myself indignant at tiktoks that personify their cats to laugh at how silly it would be to drop everything and chase after a laser pointer. You wish you could lock in like that! At some point this year my preference to eat alone, and be alone most of the time, disappeared. At some point my fear of texts and emails and phone calls also disappeared. Just like Pumpkin runs to the window when there’s screaming outside, I find myself instantly opening client feedback emails without holding my breath. What was ever so scary about seeing or knowing or discovering?

Elvia Wilk: This year I had a wedding and that's the hed, dek, and lede. It continues to be THE breaking story. AMA if you are interested in hearing about my husband(!?) Btw I found out that you do not need to get legally married to have a wedding and you do not have to say husband unless you feel like it.

The other best part of the year was teaching. The students were beyond, and made me care about everything (or at least somethings) again. My fall class was on PORTALS and I can send you the reading list if you want. Book-as-portal is the motif of the year, because there must be a way out of all this right?? I also finished writing my own portal novel, which you can read if you find a time-travel portal to 2026.

Speaking of no-way-out, I learned a lot about the US prison system by working with people stuck in it. Whatever I knew about prisons before, it's worse than that. And the more I know, the more obvious it is how many aspects of all life here are run by the same logic and the same companies.

Segue to: I got an enormous insurance payout after 14 months of a gruelling battle with Cigna. They just could not get enough proof that my shoulder regularly falls out of its socket. Coincidentally, they approved all of my claims on the afternoon of the exact same day that Luigi did his 7am shooting. Huh.

My personal 2024 syllabus was stacked. My favorite find was Jacqueline Harpman’s I Who Have Never Known Men, which is going to be the starter pack for my class next year: LAST WOMAN ON EARTH. In order to counterbalance, I then decided to get to know some men writers who I somehow... skipped over until now. Slammed down a ton of Camus, McCarthy, Mann, and Roth. Honestly, tasted great.

In new books: Tony Tulathimutte’s supremely rejectable masterwork, well paired with a Roth binge, Emily Witt’s very important Health and Safety, which made me think I maybe CAN stay in New York, Jennifer Kabat’s extremely beautiful The Eighth Moon, which made me think I maybe CAN leave New York, the endlessly looping Solvej Balle duo (also fits in the LAST WOMAN starter pack), Robert Plunket’s Love Junkie (HAHA), Leora Fridman’s Bound Up, finally the smart-smart kink book you didn’t know you needed, Atossa Araxia Abrahamian’s The Hidden Globe, a book you can gift to every person in your life, Garth Greenwell’s unpleasant yet lovely Small Rain, which goes even better when paired with ummmm Luigi Mangione, Isabella Hammad’s Recognizing the Stranger, which of course you must read.

As every year, I returned to Carrère; this year it was The Kingdom and The Adversary, both of which I prefer to stay up all night reading, and the Strugatsky brothers, who also deserve to be read at night. If you happen to be an insomniac who reads German: Theresia Enzensberger’s Schlafen is the genius company you need at 4am.

Top movie was hands-down Conclave. Moar pope.

Acknowledgements: Thank you to my group chats, writing group, and La Becque.

H. Sinno: There’s a movie from my childhood called Bedknobs and Broomsticks, where an “amateur witch” is made to take in three unhoused orphans fleeing the Nazi attacks on London. She then bewitches a bed with a spell she procures through a mail-scam school of sorcery. Upon thrice twisting the bedknob, or maybe thrice tapping it, the group is transported sur lit across space-time, landing in various scenarios and alternative worlds.

I find myself under something of a similar spell—the extremities of my known universe curling up like anhydrous volutes ruffling around the foot of my bed, which looks like a Tracy Emin installation, the unwashed sheets furnishing forensic evidence to my ability to eat but not cook, or even make decisions about what to eat, and thusly ordering a burger once a day for months on end, and rarely leaving my bed, but to travel to Nick’s couch and similarly rot. I went to maybe 3 or at most 4 exhibitions, read nothing, and made no remarkable observations about the world or human nature, other than that salad is now more expensive than burgers, and laying down for too long is bad for your back. I curbed my consumption, mostly out of necessity (I am unfortunately not pretty enough to make money from bed), but still bought a new set of black bed sheets (they’ve had to suffer an inordinate sum). I wake up, load instagram, read about Palestine and Lebanon till it’s time for a very late dinner, and by then the day is over, and I have once again not worked out, or washed my face. Time is not a friend.

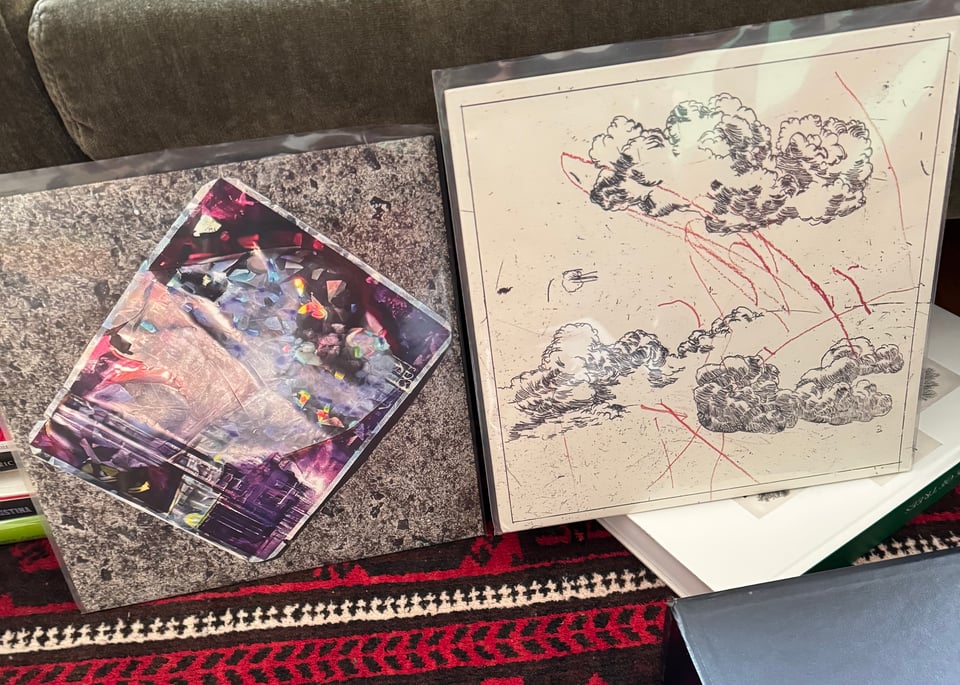

Sandy Chamoun, Anthony Sahyoun, and Jad Atoui released what I think is the best record to come out of the Arab world in some time. I won’t pretend to have a rubric other than my own fascination: it is a wartime ketamine trip sonified, and I believe it to be as close to perfect as a record can get. What it does with time is remarkable. The grid is inaudible, while the vocals stretch out syllables and phonemes in places and then turn them into rhythmic gestures in others; polyrhythms abound in the interplay of beats and synth melodics, but without the overbearing sense of a musician attempting to demonstrate a music degree. These gestures are there to articulate the temporal fissure that a war portends: war is an event that folds time such that there is always the before and the after of a war, but the war itself—the time of it, is unspeakable, because it is timeless. For the most part, we go about making music trying to turn time into sound, working around bars and measures and Ableton grids, flirting with the laws of physics trying to defy the inherent ephemerality of sound (and perhaps life), but there is something so captivatingly True about their album’s leakages across time. It is as though one is listening to music made out of time (meaning exterior to time), because its time is already over, or constantly confronted with its possible end.

I suppose the concept of time has always been a little slippery, but time under neoliberalism is now viscerally strange to me. How is it that Charli XCX’s Brat came out in mid-June? That was only 6 months ago. It feels like it’s been around for years already. How is it that the genocide is entering it’s third calendar year? How is it that this is still happening? How many Boeing whistle-blowers have died? How are we having a second Trump Presidency? How the fuck was Kamala actually the Democratic candidate? How was all of that this year? I spent my year designing and arguing about graphics for the movement for Palestine, which I’ll never be able to put in a portfolio because I haven’t “really” been a designer since 2012, and because apparently having a moral compass makes you unhireable. I got arrested twice and spent a night in jail. Time didn’t make sense then either, passing slower than a kidney stone. I haven’t spoken to most of my friends outside of the movement all year, because I’ve been in bed, and a couple of days ago I found out my friend had a 6 month old baby. That baby has been around for as long as Brat, and I had no idea. Does anyone even remember the aliens still? The pope finally gendering us correctly as faggots? For fuck’s sake this week alone Carter died, people started trying to canonize him as though him having decent politics on Palestine made everything else he did completely acceptable, which is of course a similar refrain used for Assad who finally fucked off, meanwhile the US is still doing fuck knows what in Syria funding fuck knows which Islamists, while Cowboy Carter Beyoncé is waving a giant American flag on a horse (this country’s inability to grapple with just how tacky its nationalism is never fails to amuse) and of course if you point out that she’s a propagandist and that black capitalism is still capitalism you’re an enemy online and an absolute racist.

I’ve had to move through 4 houses and just as many beds, but the bed-rotting behavior is constant. How is it already December 31 and you’ve asked for this to be submitted by today and so I’m ranting incoherently trying not to be disappointing, which is also probably a good title for my memoir, which I’ve made very little progress in writing because I was busy being in bed or organizing or organizing from bed. I know that the issues are external, and that adding one more pill to my already extensive string of morning prayer beads is not a solution to genocide, capitalism, housing insecurity, inflation, unemployment, or watching your home country get decimated by your own tax dollars, but it was either I get out of bed or I burn the bed with myself in it, and I can’t allow my mother to outlive me. It is the one thing about time that has to make sense. A couple of weeks ago I got out of bed and took my Pristiq for the first time in about 5 years. I’m late to the gym so I’m going to stop ranting now. I apologize for the typos and inefficiencies. I’m bad with time, but I love you very much.

Mary Kate O’Sullivan: Every time I have tried to write this, it ends up being a diary entry. The thing is, I actually don’t want to share anything about myself this year. Free Palestine, Free Luigi, and let every union align our contracts to expire on May 1st, 2028. Amen.

Tiana Reid: Fuck, fuck, fuck. Or, as June Jordan wrote six weeks after 9/11: “Sometimes I am the terrorist I must disarm.”

Emily LaBarge: It’s icy in London and I have to say I’m glad, relieved, refreshed (you can take the Canadian out of Canada), dragging home the last bits of groceries as the wind whips about dramatically. Colder: I want it colder! Last night after dinner with my parents we went to the pub for a nightcap and watched as two rogue foxes, one limping, ran through the empty streets of Blackheath. That one’s me, I said, but I can’t remember if it was aloud or not. Inside, a decent young pianist played a small Christmas repertoire before moving into Bublé-style jazz standards. How to sum up a year? It took me 10 months to start writing 2024 instead of 2023 and I wonder how long it will take for 2025 to settle in. Time has been different, obliterated, deranged, for so many reasons: genocide, personal loss, never enough of anything, except repeated attempts at joy, which, I’ll admit, arrives when least expected. Texting with nullities. Talking to Kate every day. David sending rare snippets of writing. Orit cooking whole cauliflowers. Finishing my book. Megan’s paintings. Tai’s voice. Loving Brian. This feels like one of those lists you make about how to be grateful when in despair and it is a little, since I, like you, live in the inescapably violent, despairing context of the world. Comrades make the bad infinity less bad and that’s perhaps enough, or what one can hope for, when can one muster hope. La lutte continue. “J’EXISTE” reads a sticker on a phone pole I pass by every day, just before the freestanding sign on the back of which someone scrawled, several months ago, MERRY CHRISTMAS. No time like the present. Elliott Smith was just playing on the radio and then Ryuichi came on: feels like a cosmic place to stop writing. Love you Sasha. Free Palestine.

Montana Simone: Every year I try to learn something that feels a little scary. In 2021, it was learning to drive stick (in an ’86 pickup, up Yosemite). In 2022, it was welding and metal fabrication, and getting work in some dream studios. In 2023, I figured out how to long-distance backpack, tackling a section of every long trail in the country within the calendar year (ok, nerd).

2024 was less of a launching pad and more of a crash site. Everything seemed meaningless in the balance with genocide, as we peered into our screens and at our selves and through our communities in Palestine, Lebanon, now Syria and Yemen, claiming and counting. All my work became counting, the bodies that didn’t get out, the food that didn’t get in, the unnamed and unwhole, unburied, unclaimed… I was scrolling and stimming away sculptures in my studio and everything came out an abacus of death.

The hostility and abuse that New York City meted out to those trying to do anything to stop the US and Israel from wiping out an entire people was also eye-opening. It was a strange year to be making a piece for a New York City park, while my friends and I were getting chased and beaten by its cops. But it was in keeping with the absolute failure of the liberal establishment (see: dead people), and the dems had no clothes, and the lords of tech assembled court around Trump.

So in 2024, I learned to organize large groups of people in ways that allowed their talents and passions to flourish, while finding ways to protect us. We succeeded and failed in many ways. We prefigured, accompanied, and felt a great deal of sadness, fear and anger that couldn’t be rationalized or taken responsibility for. As every new day broke us open, we learned to alchemize rage and sorrow into solidarity and action. I’m ending the year in burnout and preparation, grateful for the guidance of Staughton Lynd, “[…] beyond the [fear-need dilemma], imagining a transition that will not culminate in a single apocalyptic moment but rather express itself in unending creation of self-acting entities that are horizontally linked, is a source of quiet joy.”

Zac Hale: I can’t stop looking at these pictures of Victor Wembanyama playing chess in Washington Square Park. I also can’t tell if he is winning—I’m choosing not to look into it. This January we watched him lose in Memphis, two days before his twentieth birthday and four days before Ja Morant’s season ending shoulder injury.

I haven’t always loved Memphis as a city but I do now. I don’t have a lot of hope for the immediate future but I remain a pretty hopeful person in general. In February I wrote a paper about evictions that I kept having to revise because tenants kept getting more organized and winning more rights. Sometimes I think rights are something you fight to win and sometimes I think they’re something you already have and that’s why you fight. It’s the same either way unless you believe in god.

Things are incredibly bleak and there really isn't a clear counterpoint, but there are moments that break through for whatever reason. An earthquake, an eclipse. Wemby hunched over the chessboard in the rain.

Sierra Pettengill: My father died, wounded, destructive, close on the heels of my mother. The cop outside the house was unbelievably young; I couldn’t take my eyes off his wide bloom of acne. I rended my garments. In a mistral, we hiked up to the sailors church in Marseille, la Bonne Meré. The best paintings I saw this year were there, anonymous 19th century ex-votos: two nuns lined up near a cross-sectioned train crash, midnight waves breaking over a shipwreck. I hoisted a sail at the wrong time and drove us, hard, into a buoy on the Long Island Sound. I tried to hide on the bow, but let the sailor from Marseille see me cry. Everyone was talking about mourning and grief, or at least writing those words.

When did everyone start using “capacious?” I read it over and over, littered through every essay this year. It described both violences and artistic scope. It felt like a word determined to avoid setting limits. Its ubiquity made me uneasy; our writers so unable to wrap their arms around things. I collected my baby teeth from my mother’s underwear drawer. My true love fabricated a clock whose hands are made of teeth and snuck it through international customs. I filmed Super8 in a 10th century monastery in Georgia and 16mm in a pantyhose warehouse in Queens; an old man’s childhood memory hallucinated when thrown overboard in the Southern Ocean, and the fur coat my great-grandfather made on 33rd Street for my mother’s 16th birthday, respectively.

Lucy Sante: As I noted in my 2023 entry, every year outstrips the previous one for terror. 2024 was no exception. I mostly stayed away from the news, because I’m old—I turned 70 this year—and there's not a whole lot I can do, and because I need to stay healthy so that I can write the two books I have in the works. Doesn’t much matter after that. Right now we’re in an eerie historical antechamber, waiting for the start of misrule. Everybody I know is weirdly calm about it, probably for the same reason I stay away from the news. Personally it was a strange year, too. I spent a great deal of it being interviewed about my book, and it never felt repetitious to me. But even as my book did surprisingly well, my mood plunged ever farther down. As every trans person above a certain age will tell you, there’s no loneliness quite like that of being trans in a social vacuum. There’s no way to turn the clock back to when I might have been trans and also had a life. I kept thinking of Little Richard's “He Got What He Wanted (But He Lost What He Had).”

Charlie Markbreiter: 2024: it broke me, and then it broke me, and then it broke me, and then it broke me, and th—

Aria Aber: Last night I dreamt of my friend to whom I dedicated my forthcoming novel—we were stuck in a subway station with malfunctioning trains. What was this subterranean spectacle? He’s been on my thoughts for years now, he died by suicide in April 2020, thirteen days after my birthday. He was smiling in my dream, but as is always the case, he did not speak. I wept while standing in line for coffee this morning, thinking about his silence. He didn’t witness the last four and a half years, the destabilization of every country that’s close to my heart––what would he have said? I wish I could read Rachel Corrie’s letters to him: “Sometimes I sit down to dinner with people and I realize there is a massive military machine surrounding us, trying to kill the people I'm having dinner with.” I am thinking of my disappeared uncle, who lies with thousands of other prisoners, inside a mass grave outside Kabul. The dead were everywhere this year. The dead, and the very young: students occupying a building at Columbia and calling it Hind’s Hall. Hundreds of us, across the city, the country, even on the other continent, listening to their quivering voices on WKCR. Who do we live for? I asked myself this question every day of this year. I lost respect for many, and yet I made new, wonderful, budding friendships. I can’t really believe 2024 is ending––this was no year for me, a part of me is forever suspended somewhere inside a day of last December, hopeful that this year might be different, not worse.

Farah-Silvana Kanaan: 2024 is the year that broke me. I checked Twitter for the first time in months today. The first post in my “for you” feed said: “in 2025 we leave self-loathing behind.” I let out a half-hysterical cackle. Then I started sobbing. Softly, even though no one can hear me.

Jason Evans: Both collective and personal grief impacted my ability to function in 2024. I didn't get out as much, I barely saw any shows, I wasn't around to support friends at their openings or performances, and I fell far behind on updating This Long Century. I did read though—often orbiting around stories of sick, dying or recently lost parents: Intervals by Marianne Brooker, Divided Island by Daniela Tarazona (tr. Lizzie Davis and Kevin Gerry Dunn), Voyager by Nona Fernández (tr. Natasha Wimmer), Gifted by Suzumi Suzuki (tr. Allison Markin Powell), A Very Easy Death by Simone de Beauvoir (tr. by Patrick O’Brian), Undiscovered by Gabriela Wiener (tr. Julia Sanches), as well as the last book I read, No One Knows Their Blood Type by Maya Al-Hayyat, translated beautifully by Hazem Jamjoum (whose work on Ghassan Kanafani's 1972 text The Revolution of 1936–1939 in Palestine is also essential reading). Al-Hayyat's nonlinear story is centered around Jumana, the daughter of a PLO fighter-turned-administrator, who is forced to question both her identity and her relationship with her father in the wake of his death. Like many of these books mentioned, No One Knows... is written with a language so deeply human, yet unromantic—for which I’m grateful. I gave up booze so most days I self-medicate with poetry, in 2024 new collections by Najwan Darwish, Fady Joudah, Victoria Chang, Nam Le, Ibrahim Nasrallah, Hala Alyan, Mosab Abu Toha, Don Mee Choi, Gboyega Odubanjo, Mary Ruefle, Dawn Lundy Martin, CA Conrad, Jen Fisher and Emily Hunt, served as powerful interventions to the daily fog. Of course, it is impossible to reflect on the past year without thinking about the horrors we wake up to each morning. Over 450 days have gone by as we continue to see an ongoing American funded genocide of the Palestinian people, by Israeli forces, play out in real time through images and videos on our screens. It’s hard to reckon with such heartbreak, as so much of the world closes their eyes to this violence. Sitting with this pain is itself a privileged choice, and cannot replace the actual work needed for true liberation, but maybe as Isabella Hammad writes in Recognizing the Stranger, “To remain human at this juncture is to remain in agony. Let us remain there: it is the more honest place from which to speak.”