writing about 2025

Wasim Said:

Two o’clock after midnight.

The rain is falling. My tent sways right and left. My little brother beside me is shivering. Dogs are barking, and my hands tremble from cold and from humiliation.

I argue with myself: Now I will sleep. Enough wakefulness. I must sleep to escape the hell I am living.

It answers me: Are you fleeing from one hell to another?

The souls of those I love are waiting for me there.

I cannot sleep.

I take my pen and paper; the faint glow of my phone lies beside me.

Lightning stirs the tent—thunder from the sky, and the thunder of planes.

I decide to write that this genocide has stripped us of our dignity, and has exported to the world an image that does not resemble our truth an image of humiliation and abasement.

I begin to write…

Suddenly!

A torrent of water destroys the tent, floods me and my brother as we lie on our bedding, and ruins everything I own.

I continue writing on my phone after losing my papers. It is three in the morning, inside the tent of one of my relatives. The stench of his little daughter’s urine chokes me—he is unable to provide diapers for her; he can barely feed her. It is the only tent in our camp that is still usable.

Twenty of us are inside it.

My clothes are soaked. I shiver, and I remember…

How the water forced its way in from the right side of the tent and destroyed it.

How it drowned us.

How my brother jolted awake in terror, shaking.

How he called me by my name—pleading, afraid, in need.

And I was silent, trembling, powerless…

Powerless.

Powerless.

Powerless.

My father’s face. My mother’s screams. My siblings’ cries. The pleas of our neighbors in their tents, the crying of their children.

The sounds of rain, of thunder, and of the thunder of planes.

What was I like as I stood in the middle of the camp’s street, the rain pouring down on my head—or, to be precise, it was the bombs of the sky that were pouring down on us. As for the rain, that was what used to fall on our trees, when I was in my home, with my family gathered around our heater, watching it and enjoying it…

The water reached just below the knee.

A man screaming at the sky, begging it, asking for its mercy—then breaking into hysterical laughter.

A wife screaming at her husband to take their newborn child and protect him…

He shouts back at her to be silent and wait for the verdict of fate…

His shouting to conceal his helplessness.

A cold, trembling hand pats my shoulder: Come on, my son.

Come back to the tent—you’ll fall ill if you stay.

My father walks ahead of me.

I walk behind him.

The sound of our feet struggling through the water.

The sound of our thoughts struggling.

I could hear what was turning in my father’s head

exactly what was turning in mine.

We enter the tent. Before me are my younger siblings, my mother, my grandfather, my relatives—everyone soaked, bewildered, broken, crushed, despairing…

Suddenly!

All the sounds around me fall silent, even the sound of my thoughts,

even the trembling of my limbs and the pounding of my heart.

And one question echoes:

Am I human?

Are they human?

And it is still echoing….

Reality is bitter.

Extremely bitter.

They are literally monsters.

(Wasim Said is the author of Witness to the Hellfire of Genocide, and is on X here. He manages this community fundraising campaign. Please give whatever you can.)

Neeraja Murthy: I’ve been thinking about the instinct to just run away during the second full year of genocides. Every settler ran away from something, no matter how aspirational their story. I challenge my mom all the time about why she came here and created Americans and she always tells me there were much better opportunities here. I used to see it as such a brave journey, but I now understand the abject fears that present themselves as careerism. I still showed up to work during the second full year of genocides. So many of my best childhood memories are a capsule of the isolation of growing up far from the family home, alone in my bedroom. The death of D’Angelo in October transported me back there at age 13. Voodoo was one of the first albums I pirated when I stopped buying CDs. I thought I found the hack because I got to explore so much music for free, but now I have to derive my taste from scratch over and over because I can’t physically peruse what would have been decades of curation. The forced destruction of memories and built worlds overseas maybe wouldn’t be possible without our chosen destruction of our own memories and built worlds here.

D’s abrupt final delivery of “how. does. it. feel.” preceding the ethereal instrumental leading into his sweet lullaby-like vocal “Africa is my descent, here I’m far from home” is a thought structure I've calcified as a note to self to counteract the instinct to run away. Connect, get close, and use the bond to build an altar at which to honor alienation and suffering rather than let it lead to despair, then use this as foundation to build a world that remembers what they want you to forget.

Tiana Reid: Mostly time blurs but I will always remember 2025 as the year of Melissa, the category five hurricane that hit Jamaica in late October, a week or so after my first visit in too long. I keep writing and deleting things, mostly about my family. I fear my severe self-editing is not the point of this but maybe I have nothing else worth sharing. Nothing I want to share. Or maybe I just can’t get into it. I’m sorry. But then I think: 2025 was not like that at all. I tried, but not hard enough, to be radically open to sharing, to that which we have in common, which sometimes is not very much at all.

Eli Coplan: It's January 2nd and it's already dark out. I’d told myself 2026 would be the year I’d finally stop procrastinating, but now I'm trying to build a thermoelectric freezer into a 1960s drum set in three weeks. The idea being that with enough cooling units, high amperage, efficient heat transfer, and the right set of connectors, the drums could grow cold enough for a layer of frost to form upon their surface from the air.

The frost is transcendent. It shimmers in the light. It's like snow but it doesn’t fall from the sky—there’s enough water in the air. Heat is pumped from the surface, then absorbed into liquid coolant and cycled out through an advanced German radiator, where it’s dissipated into the air. (This drum set is a fountain.) I spent every day of the holiday season ordering parts online. Three Canadians helped me smuggle the radiator across the border. This feels myopic, but most of the time, life in New York is pathologically social and I’m enjoying a short break, buoyed by the promise of socialism.

2025 was the year that the Whitney Museum destroyed its Independent Study Program (est. 1968) in service of Zionism. Later, while phone banking for Zohran, amidst more heartening experiences of democracy a man I dialed informed me that I was a Nazi and that he would be coming after me. His name is David Carey. Google revealed him to be the senior vice president of public affairs and communications at the global media company Hearst, as well as a current trustee of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

This drum set has something to do with the forces of nostalgia that govern collective will, or that seemed to until this year (the object world remains a gerontocracy). For now, I’m in my apartment reading about the thermal conductivity of various greases to try to reckon with the passage of time. I went to sleep around three telling Sasha I’d send this in the morning. I woke up and we bombed Venezuela.

Rosie Stockton: This was a year I learned to stop mistaking the result and the cause. Spinoza taught me that. Found the space between immanence and transcendence and ran out of gas, shifted into neutral, tried to coast. Slowed down the timeline. From the perspective of infinity, it was Real aftermath hours. Just because you can take something apart doesn’t mean you can put it back together again. Engines, butterfly wings, love. Cared less about the heart than the blood running through it. Felt my own finger tips. Which is to say I got way less into formalism, way less into math. Wiled out, I could feel myself behind myself, I was ahead of thought, I was ahead of the disavowal. I was so ahead I was behind. Stopped running from and started running toward. Stopped running altogether. To know anything about love I read up on taxes. I studied debt and leverage and commuter train routes. I studied the loopholes. The history of negativity and supply chains. Did my chores. Applied myself. Had a candle lit pretty much from dawn till dusk. Went into public and was dazzled by the world, vulnerably. Drove back and forth to Chino each week to learn how to love more militantly. Colluding with the AI soil, jacked with chemicals, with fences, with Afterpay, with my friends, depleted by deadlines, weather events, a month of ash. Arsenic, chromium, and benzene, the air revolted, the political economy of staying screamed, sighed, asked for help. Bernadette said it: nothing outside can cure you but everything’s outside. Still, I panicked thinking about what the wind could do to me. Plead with my analyst to tell me exactly what was wrong with me as a birthday present, just this once, just for fun. Canst thou not minister to a mind diseased/ Pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow/ with some sweet oblivious antidote?? My friend had been teaching his sophomores Macbeth. Famously, he taught me, the patient must minister it to himself.

Ozayr Saloojee: This year, my mother’s tremor—benign, familial says one doctor; maybe Parkinson’s says another—moves her right hand, her writing hand, her touch-my-check-with-this-hand hand, her quilting hand, her sewing hand, her baking hand, her sign-my-daughter’s-birthday card-hand. The tremor moves her hand unconsciously, in flutters sometimes big and sometimes small. Her hand moves in widening circles today, in lessening orbits yesterday, last week, last month. Her hand is conducting an orchestra that she herself cannot hear, but that I imagine is beautiful.

I spend much of this year trying to notice her more, to notice her hand more, when it moves, when it’s still, when it’s holding something. I try to do this in a quiet, indirect way—she has a gentle shyness—so that it doesn’t make her notice my noticing, or make her self conscious. So, over this past year, I looked at her hands and then, incrementally, I looked at her more, trying to see her—really see her—as much as I could.

I notice her hand shakes when she watches the news. Her hand shakes when the news is so overwhelming. Her hand shakes when there is no tenderness or softness in this world. Her hand shakes when she wants to cook, but can’t, but it stills when she watches her granddaughter fry those samosas just like she would have done.

In turn, I try to think about my hands over this past year. They write a syllabus. They write an op-ed. They make drawings of canopies and gardens and minarets. They press send on e-mails that hope to find you well. I press my hand into the soft fur of my cat’s belly and feel his purr travel from my fingers and up into my shoulder. I think of my hand on my wife’s in the car, as I touch my daughter’s face to wake her from sleep. At the end of this year, just a day ago, I woke up and noticed my own hand – my writing hand, my drawing hand, my op-ed-writing hand, my year’s reflection writing hand – shake. I willed it to stop but couldn’t. I counted. Almost 40 seconds. Benign and familial, I hope.

She said—my mother—on that same day at the end of this year, looking at her own hand, at a knuckle on a quiet hand on the table in front her: “It looks like a heart. I have a heart, there.”

I had a plan for writing this reflection on 2025. It was all mapped out in my head. Then just before I pressed send to Sasha, I saw online, that in mass graves in Gaza, the Israeli occupation forces used zip-ties to bind the hands of murdered adults, youth and babies. Send.

Aditi Rao: The year 2025 dared to ask the question: “how much more dogshit can we stuff in this carcass?” I fear 2026 will answer, “piles more.”

But before the new year proves me right, I’ll live by the microbial hopes these past months offered. One came from a woman outside my door filming my home’s Palestine flag who I believed was doing so doxxing-ly. I opened the door readied for confrontation only to realize she was FaceTiming family in the Occupied Territories. “Sorry for lurking,” she said, “I just wanted to show them something beautiful.” One came when 12 of my comrades rejected an extortionary plea deal that would dismiss their charges of trespass during the encampments for the cost of upholding mine alone. We stuck it out, and in July, after 14 months of court hearings, we won, together. One came each of the 87 times I read Etel Adnan’s Arab Apocalypse. One will come tonight with the 88th.

One came on my wedding night. I got married this year to a gorgeous woman who takes the world as urgently and earnestly as I do. After the celebrations, we made our way with a train of dearests to a favorite spot. As we pulled up, we encountered a group the mirror image of our own— dressed-up, textbook diverse, and radiant. I turned to my fresh Wife and said “they must be from another wedding party,” she looked back and said, “more than that, I know that other bride.” My wife had gone to a dollhouse-sized college, the sort that went extinct a few years back when a dozen of this nation’s smallest schools were scrapped for parts by the phagocytic appetites of R1s around them. A statistical unlikelihood ensued. One of the 18 other graduates in her class had fallen in love, moved to Philadelphia, planned a November wedding, and decided to afterparty at a smallish joint south of South Street. That made two.

It was, I believe, a glitch. The universe’s plot had intended to send just one to Solar Myth that evening, but fate double-clicked. I entered married life more committed than ever to the existence of signs and omens and planetary trajectories and cosmic forces. Body doubles are also a source of hope.

If it’s decided that now is the time of monsters, let it be the time of magic too. More dogshit, nonetheless.

Ayesha Siddiqi: The greatest measure of ill health doesn’t exist in any doctor’s office or sealed spit sample mailed to the latest business advertising functional medicine. It exists in the experience of good health. For better or for worse, experiencing the alternative is the most sobering illumination of the true reality of any given state. You don’t know how bad you had it until you have it good, and of course vice versa.

As example, this year for me revealed a new level of health made obvious by which problems no longer existed in the background. The muscle developed in regular pilates and yoga evicted the pain that once lived between my shoulder blades. A more nourishing and balanced diet phased out food allergies I’d grown accustomed to bearing. I didn’t understand how poor my immune system had been until I noticed that paper cuts and bruises no longer took months to heal. In this timeline too are profound horrors; genocide fast and slow, the abdication of the commons to the highest bidder with the cruelest agenda, a goose step towards climate collapse.

Across every measure; social, political, environmental, we are facing extermination and offered the illusion of choice between being either a victim or agent of fascism. I wrote about how a disproportionate fixation on physical aesthetic markers has become the dominant response to this terrain of threat, especially among those most responsible for it. Residents of the imperial core are retreating into the seemingly more manageable scale of vanity, justifying it as medically urgent – all while the political moment demands poses more aggressive than Warrior 1 and 2 on a spongy mat.

When daunted by the amount of microplastics and pesticides that may be entering my bloodstream I think of the Romans who drank water from lead pipes, the Victorians whose homes were painted with lead, and the modern Americans guzzling protein powders revealed, this year, to also be full of lead. What we see as “norms” are just a function of short memories (potentially a side effect of all the lead).

I know enough history to know the winners barely write it; they don't even read it. True knowing resides in comparison—which often, but not always—takes time to reveal itself. Just ask the old people that eschew banks in favor of mattress undersides or who know about which towns to never stop in when traveling alone. It won’t take much longer for their caution to be timely for more of us once again. So much has changed, so little changes.

I don’t write ‘best of’ year end lists. I don’t care for anything affirming a linear perspective of time, except birthdays. And as far as an exercise in “looking back” and “remembering” goes, it’s funny to contain it to after Christmas. When I was younger and more dramatic, or just dehydrated, I was aghast at the idea that it’s even possible to ever not be Remembering — burdened by all that has been, will be, and never be again, I didn’t want to create homework about it through lists and announcements. This year I’ve been wondering what comparisons we’ll live to make and on which side of them we’ll find ourselves.

Isabella Hammad: What to say? A “ceasefire,” a “ceasefire,” ongoing carnage. I was in New York for the first five months of the year, researching and writing. I spent a huge amount of time with friends, old ones and new ones, which was the saving grace. Some have aged suddenly, visibly. I sighed a lot in the library. I went on a book tour to too many countries and hated myself, talking on stages, I would like to stop talking altogether. I finished a novel, I still don’t have a title, I started thinking about a new novel, I taught a workshop, I remain geographically confused, I am getting woo-woo about the energies of places, I’m not sure how much of that is just the substance of my own mind: the slippery polluted air of Athens, eternal port; Palestine’s thick persistent frequency; Berlin’s grave sour history. Beirut’s frenzy. Even the buildings seem nervous in Beirut. I liked Barcelona’s southern lightness, the way everyone is always running a little late. Unlike Switzerland, where I was the only one.

Sunny Iyer: Yesterday, I finished reading Jean Genet’s Prisoner of Love, a sprawling dream sequence of his years with the fedayeen during both Black September and Sabra Shatila, interspersed with time spent among the Black Panthers. This book transformed me and I can’t imagine a better way to end the year.

At the time of writing (1970–1985), the Palestinian struggle was increasingly lonely, rife with betrayal and misapprehension. Their neighbors in Jordan and Lebanon were traitors. Bobby Seale was in prison. Genet’s “mirror-memoir” is like a retroactive antidote to this loneliness, and the uncompromising spirit that he so lovingly characterizes in the fedayeen and Panthers is “quixotic, fragile, brave, heroic, romantic, serious, wily, smart.” I think of Friendship in Friendship's Death. She arrives on earth also incidentally amidst Black September—an apparition and a witness. She is a key to peace. When Friendship resolves to join the fedayeen, she says: “Here on Earth, sacrifice has a meaning, because every day is a day of the dead.”

Prisoner of Love contends with failure, which is something that preoccupied many of us this past year. The failure to disrupt the temporality of war and the masquerading of a slight change of pace as ceasefire. The failure to make good on promises. The failure to feel totally, earnestly present. Throughout the book, Genet repeats, “trying to think the revolution is like waking up and trying to see the logic in a dream.” I’m not a pessimist! I feel ashamed that I had an exceptionally good year despite all this. My only rollover resolution is to learn how to do a headstand. If I could transform this shame into guilt, would it have more revolutionary potential?

Friendship, sacrifice, defeat, friendship. The excess of failure is the kind of love that resembles valor in desiring against all odds. I loved a lot this year. I fell in, out of, and more in love. I tear up when I think about how much I love my friends… how beautiful they all are. I’m lucky to love and be loved.

Ania Szremski: This year, the building in which I live, built in 1927, really began showing her age. So many leaks from the ancient pipes, lights flickering due to coco-jumbo wiring, cracks in the walls emerging—my beloved says that means the foundation is shifting. He gives the building about fifty years before it is condemned, which is something new for me to worry about when I’m trying to fall asleep. I always used to worry about fires, but now I can also worry about building collapse, and that my beloved will be deported, total destruction of home and family. My father, terrified by the news in the US, has throughout the year been urging us to flee to Poland, although he himself is worried about a nuclear attack there; I come from a very nervous family.

The concrete wall separating the building’s trash alley from the driveway of our neighboring building suddenly collapsed this fall, with an all-at-once thud that made our building quiver. Metaphor!

My building is owned by a man who goes by Harry, who fled the Bosnian genocide with his family in the ’90s and wound up in Ridgewood, Queens, where he bought this edifice back when the units were rent-controlled and rent was $80 a month. I have never had a landlord of whom I was not scared, and Harry is no exception, except listen to this:

We had torrential rains here in NYC this fall, and we stayed huddled up inside for a day or two, the dog refusing to go out, and I noticed some miserable-looking pigeons on the fire escape. I didn’t do anything to help them, because, honestly, what could I do? But here’s what Harry did: he noticed a particularly miserable pigeon on the building’s front steps. He picked it up and took it to the basement, where he gave it a little box to sleep in and fed it milk and seeds. When the rains stopped, he let the pigeon go. Love, amid the ruins.

David Markus: It’s New Year’s Eve and I’m thinking about something Ilan Pappé said in conversation with the Makdisi brothers some months back: “the rot is very, very deep...” He’s talking about Israel, but the words strike me as applicable to a more generalized structural decay. In the institutions within my purview, there’s not just the stink of decrepitude or corruption—something rotten in Denmark—but a sense of slowly accelerating disintegration.

The rot is deep in an academy that spent decades gargling with the language of inclusivity only to throw in with the gestapo at the first beckoning of its boards of trustees. The rot is deep in an art establishment that punishes its most principled representatives for daring to address the moral issues of our time. The rot is deep in a liberal establishment that devours the new to sustain the dying while the White House wallows in a kingdom of putrescence. The rot is deep in a society that bets its economic future on automating the remaining vestiges of rewarding human labor while further contributing to planetary despoliation. One could go on enumerating. The rot, as Hamid Dabashi reminds us, was there in the false universalism of Kantian metaphysics from day one.

Of course, if anything, Pappé’s words reflect not despair but an optimistic telos: the conviction that the fate of Zionism as a settler colonial project is already sealed. “The cracks are very extended in this building,” he remarks. And then later, of the quasi-Orwellian mediascape in Britain: “they’re…like…the dam that has so many holes, so, yes, sometimes they succeed in putting the fingers in the hole, but then other holes are coming.”

In 2025, there were some sizeable holes punched in the dams built to contain emancipatory sentiment—not least in the realm of New York City politics. What are my hopes for the new year? That “other holes are coming,” for lack of a better phrase. Which is not to limit the horizon of political action to hastening ruination. “Transpositions and upendings refuse and then reorder the world,” writes Anne Boyer, “a refusalist poet’s ‘against’ is an agile and capacious ‘for.’”

Yasmina Price: Tears and stitches. Occasionally occluded by the unreal feeling it must be a clerical error in the lifescript, I cannot escape this as the year a stranger took a blade to my face and left a thirteen centimeter reminder. I have a pocketful of superstitions but had never been moved to think there was anything inauspicious that number. Yet maybe. I find it confusing that it will soon be six months since that day and also it is no stranger than any other measure of time. Five centuries since 1492, 66 years since 1960, a few days since one calendar turned over, a few minutes to lunch.

I have most fully understood the assault not as an individual aberration but a fractal of the larger, greedier violences, that are unbidden and expected, banal and catastrophic, unevenly distributed and heaviest on the global majority. Like most nodes of pain and grief, it has been a generous teacher. It was clarifying. It was certainly strengthening of a familiar lesson, one about interdependence and interrelation and how no one makes it through this thing alone and how I would not be without my beloved constellation.

Two loose things:

1. this is a time of many, many, many monsters and calculated, abyssal, imperial lunacy

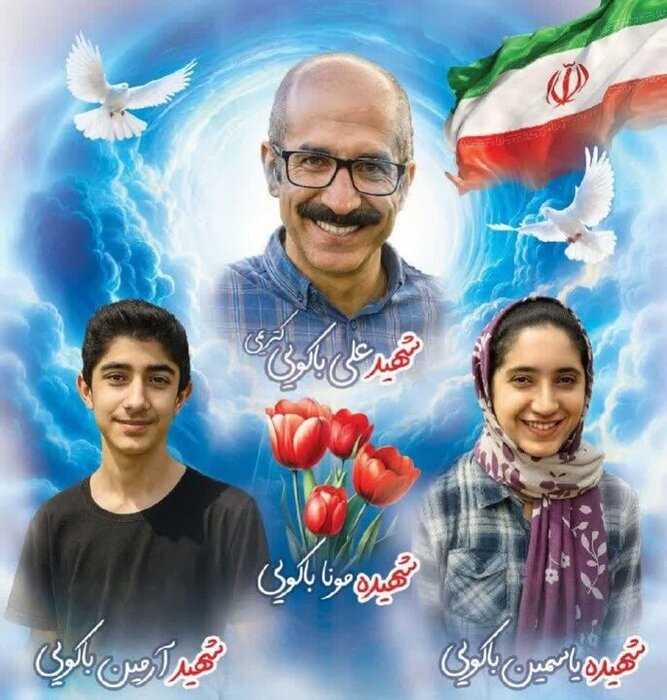

2. a shaheed, a martyr, is also a witness.

Memory and mourning walk hand in hand. We owe our dead everything. What I want most for them and for us is revenge, even as an impossible peace is likely the rightful way the compass points.

Forgiving me for fragmenting, this is the last part:

There are dead who sleep in rooms you will build

there are dead who visit their past in places you demolish

there are dead who pass over bridges you will construct

there are dead who illuminate the night of butterflies, dead

who come by dawn to drink their tea with you, as peaceful

as your rifles left them, so leave, you guests of the place,

some vacant seats for your hosts . . . they will read you

the terms of peace . . . with the dead!

— from The “Red Indian’s” Penultimate Speech to the White Man, Mahmoud Darwish (translated by Fady Joudah)

Suneil Sanzgiri: 2025 will always be the year I first visited Palestine. It was the year I felt the soil of the land in my fingers and helped cultivate and nourish the young olive and oak trees, apricots, almonds, figs, and grape vines while bombs rained down on Gaza just a few miles away, shaking the ground every ten minutes and leaving a putrid, metallic smell across the land. It was the year that I witnessed the obliterating cruelty of apartheid and occupation up close, pervading every aspect of daily life. It was the year I slept in padlocked shipping containers, unsure if the settlers would come unload their machine guns on us, or burn down the farm while we slept like they had several times before, hearing their sick, drunken singing and partying while we could feel the ground quake from the bombs. It was the year that I saw, on a clear day from the top of the hill, a bomb being dropped in north Gaza and felt its aftershock in my chest. It was the year I prayed in an ancient cave that belonged to the grandfather of the family hosting me while the roar of the Zionist entity’s warplanes shattered the sound barrier above our heads. It was the year I found out I was really good at building barbed wire fences to keep settlers off the land. It was the year I cleaned the shit out of pigeon cages and asked the family why they kept pigeons. They responded that because of the occupation and war, a lot of the native birds had left Palestine, and they wanted to release them when Palestine is free.

It was the year that when I returned, the overwhelming presence of the NYPD, the terror ICE inflicts on families across the country, and the daily violence of the Zionist occupation that I witnessed all began to blur together. Everyone warned me that coming back to the U.S. would be difficult, but I saw no difference between the brunch-going crowds across New York and the images of settlers on the beaches of Tel Aviv. It was not the first year I reckoned with my own status as a settler on stolen indigenous land, nor was it the first year I felt the weight of my complicity in the heart of empire, but it was the year that I began to make decisions on how to live otherwise and elsewhere from this cursed place. Though it will not remove the blood that’s on my/our hands, I can’t stand this place any longer, and I can’t see the violence of hyper-indulgence as anything but the dregs of the imperialist rot this place spews every day.

This was the year Abu Obaida was martyred, it was the year Anas al Sharif was martyred, the year Awdah Hathaleen was shot in the heart by the settler Yinon Levi for defending his home that I had visited just one month earlier from being stolen. It was the year that hundreds continued to be martyred and slept in freezing cold flood waters, even after the lies of a ceasefire persist, which is just continued genocide under a different name. It was the year that images of the blood of mass killings seen from space in Sudan barely made headlines. It was the year that someone I’ve been arrested with at Palestine actions and fought grotesque displays of Hindutva propaganda with since 2020, was elected mayor and made inexcusable concessions for everything he once stood for just to placate his detractors.

It was the year that I understood more about love and gratitude than ever before. Waking up next to my partner feels like a miracle every morning.

hannah baer: It’s New Year’s Eve and I’m in the busy lobby of a gentrification hotel waiting to say hi to one friend before I go to an endless string of parties. The friend I'm waiting for is unusual in several ways but one of them is that she is unusually pretty, gorgeous really, and so everyone I see is strikingly not her. Someone comes around the corner or crosses the room on the other side. Not her. Not her. What a loud part of going out to a busy party this is, looking for your person and then everyone else constitutes the shape of their absence.

If you're really focused on one thing, you find its lack everywhere. This is what heartbreak is like. It's also what it's like to live through late capitalism at the smoldering imperial core while for some reason holding onto hope for economic justice, an end to imperialist ethnonationalism, and a stranger spiritual third thing that Francois Tosquelles (who I spent 2025 thinking about too much maybe) called disalienation. In your bombed out surroundings you can feel, like a phantom limb, the organ of what's missing.

On Monday of this week I had an experience of being haunted by the absence of what I search for while watching Marty Supreme, having earlier that day wept reading Vivian Gornick's Romance of American Communism. Seeing the 1950s Lower East Side Jewish apartments in the movie where the men (including Tboymothee Chalamet) mistreat women and fight with each other about money, I remembered exactly what made me cry, 10 or so hours earlier, in Gornick's account of her childhood.

She describes being a young person watching her parents' friends, all members of the communist party, gathering in the kitchen of a small New York apartment to talk about the international situation. They were poets, intellectuals, philosophers, while also having menial jobs and, in Gornick's account, small lives. She talks about how in particular the righteous sense of historical belonging that communism offered enabled people whose lives were otherwise quite limited to feel--through their collectivity and contact--that their actions mattered and that their thinking and discourse and relating were part of something very large and very important. This is not what Marty Supreme is about. Marty Supreme is about individualism and grandiosity as a salve for poverty and desperation, a salve which ultimately fails, requiring one to take refuge in the heterosexual family. Spoiler alert? I dream of disalienated communism and I can find its lack of everywhere.

I am still in this lobby, waiting for my friend. She knows I'm coming, I texted, but she's not here yet. Should I call? There is more that we can do rather than simply wait for justice and solidarity, there is more to do than just notice her absence and pine for her. We can go out and search. We can fight injustice, and we can do creative work to understand justice, to encant justice and invoke her unmistakeable, beautiful form, not knowing from which room she'll enter but knowing, in part because of how closely we've held her in mind, that her arrival will be undeniable because she is gorgeous and not like anything else.

Laleh Khalili: What a hellish year it has been. It began with a genocide of Palestinians in full throttle and then with a fake ceasefire, the slaughter has continued at a simmer. There is slaughter going on elsewhere too: in Sudan, against boats in the Caribbean Sea, and in the detention centres of the US and Israel and their allies and clients. The chasm between the public and their leadership has never been more clear, with every institution's members disgusted by Israeli impunity and their leaders happily skipping along to the commands of the imperial metropole, the US, and its satrapi across the Atlantic. I am in my late 50s and have never felt such depth of despair, only mitigated by the integrity of the people who are putting their lives on the line (in prison cells, in protests, in direct action, and in direct resistance).

Ahmad Ibsais: There is something unbearable about sitting down to write a year-end reflection when it seems the last few years have not ended, when the dying continues, when the siege persists in slower motion but with the same murderous logic intact. I kept waiting for the right moment to sit with this grief, to process what we witnessed, to find language that could hold the weight of thousands upon thousands of my people dead, of children speaking English into cameras because they thought the colonizer’s language might save them, of fathers collecting pieces of their babies in plastic bags, of children cleaning their parents blood off the floor. But grief this large has no container. It spills into every morning, seeps into every quiet moment, transforms every celebration into something that tastes like ash. So perhaps the only honest thing to do is stop waiting for grief to become manageable and instead learn to write while drowning in it.

2026 will demand more from us than grief alone. It will require that we fundamentally change the ways we protest and organize. We cannot return to normalcy or the fiction that our city-street protests and large conferences are doing anything. We cannot accept the comfortable illusion that a pause in airstrikes while occupation continues represents anything close to justice. The cost of genocide must become unbearable. Arms embargoes that actually stop weapons shipments. Economic sanctions that hurt. Cultural and academic boycotts that isolate Israel. Legal accountability that sees every genocider and their supporter locked up. We must build the world we need rather than accepting the one they offer. And if Palestinians can survive genocide and still plant olive trees, still teach children their names, still carry return in their bodies like sacred inheritance, then those of us watching from positions of relative safety can manage the considerably easier work of refusing complicity and demanding liberation.

H. Sinno:

Ovid’s girl will

Be her mother’s son:

You will burn magnificently,

A sun you call virtue

Devotion a hunger,

A coal you grind

Into fine

Dust over blank pages

You swear have known milk.

You will do it over — committed to

The invisible translation.

Palm over parchment

Pleading for softened fiber

Sooner fire

Than believe the emptied page.

He will leave anyway.

Redact his own diaries

In the shape of a match

Then blame you for the ash.

You will wait anyway.

You would do it again.

Tasbeeh Herwees: I got really strong. I started lifting weights like it was a religion. I understood how people get taken in by cults. I turned flexing my arms into a party trick, took strangers to the gym with me. I formed calluses on the palms of my hands. I pictured myself fighting off real and imaginary aggressors, scenarios where I emerged a hero. I channeled all my displaced anger into punching the air. I punched the air again and again.

Fires followed me everywhere. In east hollywood just one block away from an evacuation zone i stuffed all of my most valuable things into a suitcase and fled to inglewood. Months later i was at a backyard party in austin and it started raining ash. Later that summer I landed in marseille to a backdrop of billowing smoke and an evacuation order we ignored to go to the calanques instead. The next month I was in Spain, biking around in a remote village in the north an hour outside of Valladolid, and i smelled fires again.

i think, when i remember 2025, i will remember the fires most. i will remember red skies. i will remember endless unfulfilled GoFundMes. i will remember TikTok videos filmed in concentration camps. i will remember the ones we love getting snatched up off the street, herded into unmarked cars. i will remember how we failed each other. i will remember how we reached for each other. i will remember the courage of my gorgeous friends, my beautiful, unemployable friends, my friends barefoot in my home, my friends piled up on my couch, laughing until i have to kick them out because im getting sleepy. i will remember danielle’s laughter in another room. i will remember helen stopping by with still-warm desserts. i will remember andrés in the kitchen, making stews and cracker crust pizzas and mixing beverages. i will remember the company of my neighbors, the nights out on the patio talking and imbibing for so long we are no longer speaking the same language. i will remember everything full of love, and i will punch the air, again and again.

Matt Longabucco: In December, I went out three nights in a row and didn’t sleep much in between. The first night I saw Nazareth Hassan’s Practice, a play in which the phrase “I am useless and that’s okay” first appears as a mantra of liberatory relief and is later revealed to be an element of indoctrination into a cult. The artist character who cynically engineers this reversal has his reasons: he’s being eaten alive by the patrons and institutions to whom his suffering is sweet, and has absorbed and weaponized their logic against them. The second night I saw a concert at the Barclay’s Center. The tickets were a birthday present for my daughter. She and I were waiting for the show to start when a woman two seats over threw up on the floor and across the puffer coats of a row of teenagers in front of her. No one in the arena could seem to locate a mop, so after having poured water bottles over slick nylon surfaces the teens as well as my daughter and I and a loner we adopted and had kept close were told to just go ahead into the pit. This is how we wound up fifty feet away from Lorde. At one point I turned around, curious to see what Lorde was seeing: 19,000 ecstatic people singing “Hammer” back to her, there’s peace in the madness over our heads, let it carry me u-u-u-u-up. The third night I watched Kleber Mendonça Filho’s The Secret Agent, a film in which images coalesce almost of their own accord to migrate through history, indigestible, passed from dream to dream, or more often nightmare to nightmare.

We’re being watched by generations, many. The archive is us, our faces. We can no longer trust our consolations, no matter how tender.

Sarah Nicole Prickett: I started having dreams set in a school with long hallways and no marked exits that turned every night into a war zone. I moved cities, choosing an apartment with an elementary school next door. I didn’t make the connection. (There might not be one.) In the morning it takes a few seconds to realize the children outside are screaming with happiness, it’s snowing again. Maybe longer, like twelve seconds—the length of time William James accorded to the ‘specious present.’ Alarmingly this may be the only time I’m alive to the state of the world.

Louis Allday: I’ve typed out and deleted the opening sentence of this entry dozens of times, unsure what to say (or not) about the past year. This indecision is not only because in the UK so many of my honest opinions are now grounds for arrest on anti-terror charges, but because beyond what is considered permissible by the genocidal UK state, more generally it sometimes feels there’s little left worth saying that’s not already been said by others more eloquent or rendered cheap by the actions of others more brave. Much of what I have dedicated a lot of my time and energy to for several years has been done in the belief that raising awareness, spreading knowledge and fighting back against propaganda can make a difference. While I still believe that to be true, it is an effort that has felt wholly insufficient and inadequate in the face of genocide. That is one of the reasons why I have spent the last year putting more of my time into trying to materially help those struggling to survive in Gaza. At times, this effort has felt similarly insufficient too in all honesty, but I do know it has made a huge difference to many families in the worst of circumstances. It has also given me the opportunity to befriend some wonderful people in Gaza. People like Samer, whose wife just gave birth and so he now has three young children to care for. His older two kids are of similar ages to my own and in moments between discussing more life and death practicalities and bank transfers etc, we have spoken about that and about being a parent. I remain in awe of his ability to carry on and try to be the best father and husband that he can be in conditions unimaginable to anyone not living through them. I feel absurd by comparison when I find myself struggling with the everyday difficulties and pressures of fatherhood and adult life.

One of the other amazing people in Gaza I've had the privilege of getting to know is Wasim who I was able to help publish his account of the genocide as a book. I was honoured to write the preface to the English translation. In addition to the Arabic original, an Italian translation has just been released and other languages, including Greek, are forthcoming. Wasim is still in Gaza and he recently started a fundraising campaign to help families around him without access to the internet and campaigns of their own, please support it if you can.

A small personal highlight of 2025 for me was fulfilling a 20 year long dream and visiting Iran. A highlight within that highlight was visiting a Zurkhaneh, an institution hard to describe concisely, but in essence a communal weight lifting and wrestling training centre that has roots dating back to ancient Persian traditions and over the last 500 years has also become infused with Shi'ism and the veneration of Imam Ali in particular. I had been excited enough simply to watch but was soon asked if I would like to join the training itself and ended up performing the entire 90 minute workout with the group's members, some of whom were well into their 70s and made the extremely difficult exercises look easy. It was a brief window into the almost comically rich, complex and welcoming culture of Iran that will last long in my memory. Within weeks of my visit, 'Israel' launched its war on Iran. Further aggression against it in the year ahead seems almost certain and it is incumbent upon all of us who oppose genocide to stand in solidarity with Iran, that is one of many things preoccupying my mind as we approach 2026.

Mary Turfah: I have been using the word garbage a lot. Will probably keep it up in 2026.

Brandon Shimoda: I was born on Hiroshima Day. My daughter was born on Nagasaki Day. She recently said: “I jumped on top of the bomb and turned it into a bowling ball.” I gave a talk on the night of February 28 in NYC in which I recited all of Hiroshima’s (many) appearances in the writings of Etel Adnan. I ended the talk by reciting these lines from Etel’s poem “Jebu” (in which Hiroshima appears twice): “Palestine is a land planted by eyes / refusing to be closed.” The talk was part of a symposium, organized by Omar Berrada and Simone Fattal, featuring talks/performances about/inspired by Etel and her work. Three of the other artists that night recited the same lines from “Jebu,” so the lines, and what they hold, kept repeating. It was clear what all of us, under Etel’s ancestral auspices, were reaching for. I keep forgetting that the line is not “planted with eyes,” but “by eyes.” What is the difference between being planted with and planted by? I think the difference constitutes a signal part of what this year has meant and will continue to mean, while insisting on the existence of those who hold, with their lives, the most transcendent part of its meaning. Two days later, I took a train to New Haven; the poet Natalie Diaz invited me to guest-teach her class at Yale. On my way, I walked through a cemetery. I wanted to visit the grave of a Japanese historian. The cemetery was empty, as most cemeteries are in the United States. It’s a facile indication of the kind of relationship Americans have with the dead, including their own, generally speaking. Snow was melting, the cemetery was mud. I shouldn’t say empty: there were raccoon prints on the historian’s grave. The class met in the basement of the Beinecke Library, which is extremely clean, with nearly-white carpeting. I forgot I was carrying the cemetery on my shoes, so I tracked mud, in cartoonish footprints, down the stairs, across the carpet, and into the classroom. I was embarrassed, at first, apologetic. But then I thought, isn’t this also a cemetery? (Also: how am I the only one?) The subject of my visit was creative research, i.e. how does a poet do research? It wasn’t until the end of class that I realized the answer was on the carpet: muddy footprints. The year kept restarting, over and over, more honestly under. It began, in part, when my friend Emiko Omori gave me a small ceramic snake, white, decorated with flowers on one side, nothing on the other side. Because it was the Year of the Snake. When Emiko was two, she and her family were incarcerated in the Poston (Arizona) concentration camp. She doesn’t remember, but she’s been making work about it her entire life; the work remembers for her. So does her sister, Chizu, ten years older (she’s 94 or 95); she organized/hosted a conference on incarceration, in Oakland in July. The snake has a long red line on its face denoting its mouth which, when looked at from above, is a smile; from below, a frown; from straight on, an expression of unnerving ambivalence. It’s divinatory that way. When I invited Emiko and Chizu to one of my classes (via Zoom), Emiko yelled through the screen “The atomic bomb was part of incarceration!” The anger of sisters who spent part of their youth in a concentration camp on a native reservation (Colorado River Indian Tribes) is inexorable, galvanizing, transcendent. The person who spoke after me on the night of February 28, was Huda Fakhreddine, writer, translator, scholar of Arabic literature. She said, “Etel Adnan showed me how to survive the narratives of war, the war of narratives. As I was trying to find my Beirut, after we had both come out of the bomb shelter and had to recognize each other in the daylight, Etel Adnan shared with me a discovery, a secret. It is possible to survive history and still live in time, all of time.”

Marianela D’Aprile: In the middle of autumn, for some weeks in a row, I noticed that the bewilderment of the new that marked my first year or two in New York City had dissolved into something else. There was, in its place, the pleasant over-treadedness of habit and the occasional sting of change. I looked at the calendar; I did some math; there it was: I have now lived here longer than anywhere else in my adult life. I spent much of what could be called my formative years not just moving around but never being sure that the place where I was was actually my home, sensing that it could be taken away from me at any moment. I never trusted that tomorrow would be the same as yesterday and believed that if it wasn’t there would be no way for me to survive. Rootlessness was both threat and way of life; I was a fish in a poisoned river. Now I’m sure that this place is my home, and it’s not just because of the number of years I’ve lived here—I’ve become my own home, too. I love this city and I love the place where I sleep at night: rent-stabilized, so as long as I hold up my end of the bargain no one can take it away from me, which is more than can be said for most deals in this life. The idea that something unknown might happen to me is no longer terrifying; in fact I’m looking forward to it.

Jennifer Lena: On the 3rd of January, my unconscious father jerked his hand out from mine as I sat hospital bedside, murmuring reassurance. He woke later that night and called my mom to tell her he was dying. She went back to sleep. Weeks later she’d borrow my shoes to cross a pebble beach and wordlessly wave his ash bag into the Connecticut River.

He doesn’t speak through me much anymore, maybe because I fled the country, maybe because I wanted it so badly. It's better than all the birthday gifts he never bought. “They may not mean to” but I think this guy in particular very much did.

Then Joshua died, and Jonathan Sterne, and just days ago my cousin Rich. My demons have started a new refrain, “it's coming for you, soon.”

Beneath my fear is desire. To better appreciate all the more life that’s happened while I was courting death, despair, jealousy. Jerking dad out of my head is the first drop in my next cycle.

2025 was the bad that turned good year. Our fascist playpen transformed me into the enemy of the state I hoped to become. Friendships murdered by Zionists opened time for new solidarities. Fleeing mutated into freedom. Regeneration left a mark in the shape of a Schmoo tattoo.

2026 predictions? The old man lost his horse, but it all turns out for the best.

Mohammed El-Kurd: Nothing witty comes to mind—this has been the worst year of my life.

Shivangi Mariam Raj: each day was spent ploughing into the infernal, searching for God amidst the rubble of this world. suffice it to say that each day was spent.

despair and speed come from the same root in latin, 'spes,' which means hope. despair is not just a loss of hope, it is also a loss of time, an inability to move forward towards death. when you lurch forward to catch your breaths, but only find your ear pressed to the grinding roar of this absence even of all form. you think of the martyrs, of those before you, of those who promised to come back but never did, and you want death because you want them, but despair is the desperation of not even being able to die. despair is the loss of all time and its end.

you begin to live outside time, you begin

to live inside

the dead and the departed.

with grains of dust stinging my eyes, stretching them from gaza to assam, from jnoub to kashmir, there was only rubble, in my memory, on my screens, smeared across my half-sleep and half-dream, all geographies caramelising into an "elsewhereness." breaking in beads of sweat, i realised that no matter where i may be in the world, i only inhabit this placelessness of "away" and "apart;" there is no now to place my feet in, everything is disintegrating, there is so much dust, there is only a promise of tomorrow, of the hereafter, of the ether which we desperately gathered with toufan al-aqsa.

each day was spent thinking of the hands that carry the killed and the stolen and the massacred, the hands that search frantically for the pulse of life on ash-smeared faces of infants, the hands that work as doctors, as carpenters, as bakers, as fathers, the hands that hold the gun to protect their people, the hands that bring candies to orphaned children scattered across khan yunis, the hands that draw architectural plans of the home that will spring from the mouth of the bombed home, the hands that clasp the keys of return, the hands that console the mourning, the hands that cup themselves and fold in prayer, the hands that carry brick, cement, and stones are all one – and unbroken. each day was spent declaring the will to be oriented towards men who fought with bare hands and with slippered-feet.

hours continue to ripen and darken on our clocks. i tell my eyes and my hands: until we annihilate them, it is our duty to keep the empires destabilised. God will follow.

Catherine Lacey: Much of the year was spent in useful confusion. I got more comfortable understanding Spanish, a process which has required me to accept a lot of chaos and opacity. I’ve gotten cozy with being wrong and staying wrong. I also started writing a novel that’s been hovering nearby for a long time, but without words—even more chaos, more opacity. I know it’s a novel because I often cry when I write it, but I never really know why.

But as I write this, I’ve entered a new kind of confusion. I have been trying to talk to my father, but his brain won’t really let us. Mainly, he repeats the same words or phrases for hours at a time. Yesterday it was “Herodotus” and “progeny” and “the grandchildren.” Earlier in the week it was “more people more people more people,“ and “large profits,” all spoken with real urgency and volume, though I think he really meant something else entirely, something that had nothing to do with people or profits. The first thing he said to my brother and me today was “God Almighty” then he reminded us that “the pain is real,” a brutal sentence to hear 15 times in a row, but later in the afternoon he seemed delighted to say, very carefully, “it is ever present, all the little bow ties.”

While talking to my sister on the phone she said she just really wants to know what he actually means, what it really feels like to be him right now, but in fact I’d really like to know what it feels like to be anyone other than me, anyone else, and maybe that’s the only thing I’ve ever wanted in my life.

It is not lost on me that I spent a solid week trying very hard to speak to my father for hours at a time when I rarely tried to speak to him at all in the last few years. It’s only now that it seems impossible to talk to him that it feels urgent that we do. We weren’t really great at conversations before his brain bled all over itself, and I have to accept that I am delusional in my present efforts.

After asking him something in an effort to decipher an indecipherable sentence he’d just uttered, my father scrunched up his face and said: “This discussion / will not/ I need it looser / if you / more loose”

I’m assuming he was trying to tell me that what he says is not literally what he means, and that when I try to latch onto the literal meaning of his words I’m just digging us a deeper hole. His brain is blood-soaked. It must be so annoying.

Sometimes, he will latch on to something he has just heard and repeat it, and after I noticed this habit I considered saying “I’m Sorry,” just so I could hear him say it back to me, for once. Unfortunately I can tell the difference between a voice and an echo, so I didn't try.

“Unfortunately” in Spanish— desafortunadamente— used to trip me up, all those fucking syllables, but now I say it with relish, as often and as quickly as possible.

Every cruelty in the world comes down to an attempt to displace one's pain onto someone else. Every form of human-created suffering comes back to that. We all have to rule our own little empires of hurt; we have to keep the hedges clipped, have to keep the populace fed and clothed, have to keep all the little bow ties straight, or else we will make ungovernable messes for everyone else to deal with.

Occasionally I spoke in Spanish to him; I’m not sure why.

Lara Mimosa Montes: I have a couple of regrets, like I’m sad I only went to one demolition derby this year. One is not enough. I know there’s always next year, but the fact that I planned poorly in this regard feels like a personal failing, like I spent too much time caring about all the wrong things. I also thought 2025 would be the year I finally got a dumb phone, but the more research I did, because I was not sure how dumb I was willing to go, the more digitally entangled I realize I am. These aren’t grand aspirations, in the scheme of things, but they do feel important. So I feel disappointed. I thought life would be different.

Sarah Brouillette: I read a book about a man who was tortured and executed because he was fighting for Algerian liberation from colonial rule. People were trying to get him released from prison. They considered him their comrade. His wife was also trying. He bonded with his cellmates. They all hated the racist French. It’s based on real events. You know what happens. You want the ending to be different. That’s the point. My dad had an accident at home and was lying alone on the ground for several days before he was found. He nearly died. His dog was at his side. I went to sit with him at the hospital. He was there for a long time. He slowly got better. We watched the Blue Jays play on a laptop. I helped him shave. I pushed his wheelchair out to the parking lot, where we faced the sun. A man in a lawn chair was playing Led Zeppelin on a portable stereo. I read a book about a young woman who lives in a town run by Mennonites. Her sister and her mother have left, whereabouts unknown. She starts getting into trouble. She could leave too, but her father is bereft and he needs her. I drove around Ottawa with my son. We listened to news reports on Mark Carney’s leadership. We listened to “Point and Kill.” We listened to a talk about Elon Musk’s tormented childhood. We listened to “Hind’s Hall.” We listened to a podcast about turning Gaza into a leisure paradise for the rich. We listened to “Bulls On Parade.” I read a book about a woman who is having an affair that goes on for a long time. After it ends, the man becomes desperate to keep it going. This makes the woman feel that she was right to stay with her husband. Her husband is respectable and kind. He doesn’t smother her with affection. I met a woman recovering from cancer treatment. She told me about a daughter she has not seen in months. No one visits her. Her sister, who takes care of her daughter, thinks it is too hard. She has no other family in Canada. She has nowhere to live. She didn’t want to leave the hospital. I read a book about two men who are obsessed with the same painting and build academic careers around interpreting it, before becoming bitter rivals. I attended a workshop about how to cross the US border safely. It is important to be honest. If you are caught lying you could be banned for life. I read a book about two women with no money and no connections, trying to establish creative careers in New York City. They have a deep, tormented bond. A good friend died. He was sick and I was planning to visit him, and then he was gone. I still think about telling him things and I briefly forget that I can’t. I read a book about a man at an interminable dinner party. He considers how people with great potential are ruined by the pressures of competitive striving. Wanting to be perceived as the best, the most cultured, the most celebrated, they become insufferable. And miserable. I went to a meeting about institutional impartiality at work. When I make a political statement, it is important that I indicate that it is only my personal view. Someone could report me for violation of the policy. My pension is invested in companies that manufacture weapons and surveillance systems. I read a book about an office worker on his lunchbreak. He is on an escalator, marvelling at the complexity and sophistication of everyday products. Like the spout on a milk carton that you fold open, or the perforations separating individual paper towels. My son stopped attending school in person. He spent a lot of time alone. He wrote an essay about Islamophobia since 9/11. People think Zohran Mamdani will introduce Sharia law in New York City. He made a video about white fears of demographic decline. He wrote a letter from the point of a view of a man looking for work during the Great Depression. I felt panicked and out of breath a lot. I slept horribly. My students wrote about romantasy as a genre of precarity, the communist-literary conjuncture, MFA credentialism and the millennial novel, atrocity visuals and weaponizing suffering, heterosexual shame. I was dedicated to one good pen pal.

Tim Lawrence: Genocide perpetrated, genocide weaponised, genocide capitalised, genocide westernised, genocide justified, genocide denied, genocide funded, genocide excused, genocide normalised, genocide rewarded, genocide legitimised. Every hour of every day, genocide. But if hope is under attack, is hope, what else but hope? US hegemony is collapsing, Europe is a zombie, the “peace plan” is a charade, politicians and Zionist fanatics have lost control of the narrative, knowledge of the colonial/geopolitical underpinnings of Zionism has never been more widespread, the global solidarity movement is unprecedented, the global solidarity movement is unprecedented is here to stay, the Palestinians will continue to lead the resistance. We cannot relax until there is justice for the Palestinians and the politicians, financiers, media executives and corporate executives who’ve enabled the genocide face justice! In-between protesting against genocide, removing my financial support/patronage from companies that are complicit with the genocide, writing about genocide, insisting on the need to talk about genocide, continuing to refigure my understanding of the world through the all-encompassing prism of genocide, I’ve been working hard on a book that gives me hope and additional direction, plus podcasting, hosting parties that allow for the flowering of collective joy, and spending time with loved ones. Free, free Palestine!

Lucy Sante: Lying low and working has been my vibe for the year. To some degree that has alleviated the sensation of being crushed by everything in 2025, beginning with but not limited to the current administration. Like I assume most people here, my anxieties were much relieved by the election of Zohran Mamdani, especially as it coincided with the obvious decline of the used-car salesman at the head of the government and the incipient fracturing of the MAGA web. I’m furiously knocking on wood, and I’m taking that little bit of optimism and wearing it for all it’s worth.

Francesca Kritikos: In 2025, reality became less cooperative than I would have liked it to be. I will turn thirty years old in 2026, and I am glad to be entering this new decade of my life with that expectation of dissidence and turmoil. Alors, c'est la guerre.

Chris Hontos: Smoke them while you got them. It was the year I finally watched Where Eagles Dare. It was about time and about time for a lot of other things too. Smoke them while you got them.

Certain types of love only exist in a rarified ether of air, and it's important to know how that air feels in your lungs. I don’t know if I figured anything out at all, but the chord eventually gets resolved.

Richard Burton is sort of like a stand in for who I was, Clint Eastwood a stand in for who I want to be one day and half the Nazi army a stand in for the cough I’m still trying to shake. The world creates and then chokes up lungs, and it has a sick bag on its head. You’ll annihilate half a pack of American Spirits if you have to.

Peace comes to us in some of our dreams sometimes, and that’s pretty good.

JoAnn Wypijewski: The surgeon who performed the second operation of the year on my left hand made an incision that lengthened my life line. I admire the worker’s graceful skill but have mixed feelings about the metaphor. Life is not for the weak. The enduring personal mind picture of 2025 – moving image, actually – is of me slipping on a bit of wet moss at a mostly dry waterfall in August and coming down hard on rock with arms bent back, shattering both wrists. I had just said to myself, above a whisper, ‘I hate this place.’ Now I howled like a wounded animal, which I was; I am. It was as if nature had roared to remind me of the frailty of puny life.

The enduring political image is the spectacle at 26 Federal Plaza in Manhattan early one spring morning. At one end of the building the sign above the entrance read ICE Check-In. Nothing more needed signal that the souls solemnly amassed, waiting for the day’s business to begin, were doomed to deportation. Outside the front entrance, people with court dates – most, possibly all, of them asylum seekers – slowly filled the plaza, a snaking ribbon of humanity, some dressed for Sunday, many with children scrubbed and groomed, and not one of them white. I was there with a Spanish-speaking friend who was handing out palm cards in many languages to inform people of the latest ruse the government was using to trick them into foregoing their rights. My friend was having animated conversations. I was reminded that ‘English Only’ has been promulgated in part to lull the native-born, to keep us stupid and alienated. ‘Parlez-vous Créole?’ I asked random black people in line, ridiculously, since even if I were able to recognize Haitians by sight I couldn’t have said anything more in French, which I’ve forgot, let alone Créole. No one answered Oui, though there was the bundle of cards in Créole I’d been given to pass out so I pressed on along the line. I was trying to help, a useless sort of help in a year when the government’s function was to make the masses feel impotent. Inside, court stenographers dressed down and went badgeless, supposedly to protect them from our small band of community witnesses. We were lectured against using phones while plain-clothes ICE agents broke courtroom rules without consequence. Their masked cronies, men and women in camouflage armor stationed menacingly by the elevators, hand-cuffed then-mayoral candidate and city comptroller Brad Lander the first day I went to court, as community witnesses recorded the scene and shouted ‘Shame, Shame.’

Months later, winter now, a church lady at an anti-ICE training regarded my bandaged or splinted hands and said, ‘You might not want to be doing this just now.’ She gave me a whistle, as she and a group of seemingly mild-mannered people talked of disruption, replaying a scene that has been occurring quietly all over the city and the country. Eventually, puny life also roars.

Samaa Khullar: “Grief” is the only word that encapsulates this year.

I’ve been thinking a lot about something my mother once told me about when she first saw the photos of the Sabra and Shatila massacre in the newspaper as a teenager. The carnage was so brutal it’s still seared into her memory 40 years later. She told me no one in the community celebrated any Eids that year out of respect for the martyrs. If that one massacre rightfully deserved the mourning and respect of the Arab world, Gaza demands that we stand still, stand silent forever. We will never be able to properly grieve every life lost in this genocide, and now, that small notion, the basic act of mourning, has also been ripped away from us by Israel. Moving on feels like betrayal. It feels like we are leaving our martyrs behind, only to be remembered on the anniversaries of their deaths.

I think about myself 40 years from now: how will I explain this time to the next generation who didn’t see it in real time? Perhaps I’ll describe the moments that felt like slow-motion. The numbness followed by guilt. The disgust. The crippling anxiety. The grief. The grief. The grief.

I hope and pray — despite the continuous disappointment of the past two years — that this time next year, I can say our people were finally able to breathe and rebuild.

Abdaljawad Omar: This year a new frame entered the frame of my being. An intimate confidante told me, with her straight face and her big hazel eyes, "I am only a suggester; you are the decider." When I first heard her sentence, it sneaked up on me. What is it to decide, when decisions have been made, are being made, and will be made on your behalf? The word lingered like dust in a sunlit room—visible only when one stops moving and looks closely, investigating that veil of dust that reminds one of the barrier windows like to pretend they are not. Decider. It sounded heavier than it should, like a crown placed on a neck untrained for such balance or glory. I carried it with suspicion.

For years, we Palestinians have inhabited a pre-scripted architecture: corridors crafted elsewhere, doors labeled in advance, exits that masquerade as options. Outcomes arrive already stamped, issued from faraway capitals, while decisions descend through Israeli interfaces—software thinking for humans, algorithms anticipating our moves, Artificial Intelligence rehearsing our lives and determining our moment of death. Choice, in this regime, becomes a hollow ritual, a theater of consent: you are invited to sign, politely, knowing the document was finalized long before you were even conceived.

The arrival of a new year in Palestine and elsewhere is also the arrival of a long list of deferrals—those things we have already decided to quit or leave behind, the items and relations we claim to be ready to move beyond. Yet they linger in our dark attics, neither fully with us nor entirely outside of us. It is also a time of reckoning with the self: with the things we have done, with the things we still wish to take up, and with the things that haunt our sleep, reminding us of our personal failings.

Antonio Gramsci hated New Year's, because for him every day should be a reckoning—an invigorating reckoning with the self. Every day should be a new year: reckoning with the past, the ability to take up, to abdicate, to escape or confront or move on.

It is the day we, too, should hate, because in our coded, algorithmic, sliced, racialized, and surveilled lives, decisions and suggestions have collapsed into one another—a collapse that is itself decided, suggested, pre-scripted into the interface. The only decision is to unmake this order. But unmaking carries its own cost, heavy and dreadful, a weight that refuses the fantasy of clean breaks or revolutionary purity. Here, the regime offers only one suggestion: resist or surrender, die or die. It is a reckoning that wrecks—not metaphorically but materially, concretely, through rubble piling up across emptied streets, a decision already taken every day, and placed on repeat. Here the suggester and decider collapse onto each other, and the decision is always the same: a wager on the perhaps of freedom. In 2025, that decision and the debris of the attempt to annihilate the Palestinian people linger. They remind us that we live in a world where neither the decision nor the suggestion is fully our own, at least not yet.

Lindsay Turner: In my head the year 2025 started in August, on my forty-first birthday, with death. My dear friend the poet Stéphane Bouquet died after a short illness and I saw my father, who had been ill for years, living for the last time. The next time I saw him, my father, he was dying. He passed away in October. The enormity of death coupled with the ecstasy of life—my joyful son turns two in January—has made me feel more unhinged than usual. Every single act of caring for my child since his birth—feeding, administering medicine, calming, shushing to sleep—is intimately doubled by this act’s negation, by the impossibility of doing these things, in other places, and especially in Gaza. How to hold it all together? No one has any idea, I know. Sometimes this feels like the only question there is.

Of course the year didn’t start in August: in April we went with the baby to Los Angeles where he ate pancakes and charmed the Silver Lake playground scene, and then we took him to Paris for July, where he ate baguettes and couscous and watermelon from the Belleville market vendors and fell in love with sandboxes in the Buttes-Chaumont. I wrote a bunch of poems but read few, saw maybe one movie, listened only to the music my friends sent me. I found great pleasure and energy in contemporary novels by women, though: books by Claire-Louise Bennett, Makenna Goodman, Caren Beilin, Joy Williams, Olga Ravn, and many others helped me imagine what a response to this world in writing might be—a response that has some counter-pressure, that pushes back, that explodes things as they are. And running through my head, even before his death, were Stéphane’s words to me in an email (subject: "tristement") after his sister died in mid-January ten years ago: because life continues, and because it’s the beauty of life always to continue, I wish you all a happy new year.

Will Harrison: 2025: the year I quit smoking weed; the year I moved out of Bushwick; the year I stopped shitposting. It was a squalid, repulsive, disquieting year, and also the first year of my life spent entirely in love. And while a lot changed, both around me and within me, it was a year that was dominated, like the last several have been, by a compulsive engagement with images. I saw anthropomorphic war planes dropping bombs and disgraced mayors smoking hookah and Chuck E. Cheese in handcuffs and MLK drinking a Slurpee. I watched fact blend with fiction, I watched the Epstein files redact and unredact themselves, I watched the footage coming out of Gaza slow, thin, and sometimes fail to arrive at all. I watched snow fall outside my parents’ window as I type this, and I watched the sun send rainbows dancing fleetingly upon the walls.

Lara Sheehi: I’ve been thinking (and feeling) a lot about the power of having one’s heart seared; about revolutionary love and the imprint(s) it requires that I/we must feel fully so it is not stripped of the political power it can harness. This is not professional brooding. I am here out of political demand. I feel the knowing ache, the visceral knowledge, of the affective connectedness that is needed if the world insists we remain inextricably tied up in affective states that detract, derail, and displace this searing pain through the empty promise of relief. Relief through looking away from Gaza; through compartmentalizing Palestine into a Strip, a Bank, a series of ’48 and ’67 Borders, an Occupied Eternal Capital and a floating Al-Aqsa, even if it brought The Flood. Relief through enforced amnesia of the forever wars of US empire that have always engaged in extra-judicial killings, whether in Venezuela or Iran. Relief through dislodging us from history such that every moment feels unprecedented; as though the kidnapping and tearing apart of migrant families are freshly pruned phenomena of imperial and settler colonial violence. Overwhelming, atomizing relief meant to crush us under the misplaced belief that our struggles must continuously be invented from scratch because they constitutively failed on arrival. This is the relief of dysregulating psyops. The refrain in my mind goes: “Your heart being seared is inoculation against disavowal”. It matches the rhythm of ache and joy, among other feelings.

I have been thinking about how allowing one’s heart to be seared, to be imprinted through the expansiveness and depths of revolutionary love, is to live with a psychic and emotional register that refuses to be subjected to the forgetfulness on which oppression relies. By living, feeling, and importantly, enduring, with a seared heart, Khaled Nabhan’s روح روحي –soul of my soul—is not just an affective fetish exported from Gaza. Or an extractive emotional device from which we can derive warmth. Or an offensive reminder of the humanity of Palestinian men. With a seared heart, روح روحي is a provocation that reminds me that the revolutionary struggle, especially if it is fought with the fiercest revolutionary love, is one in which life-making and loss are coterminous imminent possibilities. In their most powerful versions, they have the vertiginous effect of one’s (my) heart swelling and shattering at once, multiple times a day sometimes, as we yearn and fight for things that may never come to fruition. And yet, they still matter deeply.

This seared heart of mine has been acting as a stunning reminder to fight against the demands that we vacate our affect, numb ourselves, “rest,” excise the risk that threatens to unbind us, as my comrade Avgi always reminds me. In my hyper-awareness, especially now, of how my Arab Lebanese immigrant heart and body live across multiple time zones and places at once, I am reminded not to shy away from the burning hot sensation of searing. A ferociously repetitive return both to what constitutes violence so that it cannot seduce me and the presence we need to live in the fullest expression of militant commitment to revolutionary realities—now, in emergence, and in the future.

It is no wonder I have been spending more time with Walid Daqqa’s writing. His words crystallize with the power that propelled them to alchemize his prison walls: “I confess now, after twenty years of imprisonment, that I still do not know how to hate, nor to embrace the harshness that prison demands//I am still human, holding fast to my love as one holds burning coals. And I will remain steadfast in this love//I will keep loving you. For love is my humble victory, and my only victory, over my jailer.” Burning coals of refusal and defiance against his skin. Inoculation against disavowal. An imprint that defies his oppressors and connects him to his love, his land, and the certainty of (his) return, even if the form it takes is still unimaginable to us.

روح روحي tethers me to the centrality of this tenderness at the core of militancy, a lesson I had previously conceptualized mostly intellectually. With the unexpected gift of this year, with the globally connected struggles for dignity, self-determination, and revolutionary worlds, with Daqqa, it is a lesson that now lives deeply burrowed in my heart. Seared.